Chapter III: THE ELIZABETHAN ERA

Introduction

The Elizabethan era was hailed by many historians to be a golden age. However, upon closer inspection, this era was not without its difficulties, leaving many modern historians to debate to what extent was this a Golden Age. The inflation of the Elizabethan eras’ significance was largely due to the perception of failure of royal rule during the Stuart era, which was the succeeding dynasty. Elizabeth was hailed as a strong and decisive ruler who single handedly brought England into a golden age. While many still believe the early stages of Elizabeth’s reign was a glorious one, this wouldn't be the case in her later years.

Expectations of King James, her successor, started high but then declined. By the 1620s, there was a nostalgic revival of the cult of Elizabeth. Elizabeth was praised as a heroine of the Protestant cause and the ruler of a golden age. On the other hand, James was depicted as a Catholic sympathiser, presiding over a corrupt court. The triumphalist image that Elizabeth had cultivated towards the end of her reign, against a background of factionalism and military and economic difficulties, was taken at face value and her reputation inflated. Elizabeth's reign became idealised as a time when crown, church and parliament had worked in constitutional balance.

KING JAMES

The Battle of the Spanish Armada

The picture of Elizabeth painted by her Protestant admirers of the early 17th century has proved lasting and influential. Historians of the mid-20th century, such as J. E. Neale (1934) and A. L. Rowse (1950), interpreted Elizabeth's reign as a golden age of progress. Neale and Rowse also idealised the Queen personally: she always did everything right; her more unpleasant traits were ignored or explained as signs of stress.

Recent historians, however, have taken a more complicated view of Elizabeth. Her reign is famous for the defeat of the Armada, she encountered many military failures as well. Elizabeth is more often regarded as cautious in her foreign policies. She offered very limited aid to foreign Protestants and failed to provide her commanders with the funds to make a difference abroad. The Battle of the Spanish Armada was considered a fight that if she could help it, would have avoided.

Those who praised her as a Protestant heroine overlooked her refusal to drop all practices of Catholic origin from the Church of England. Historians note that in her day, strict Protestants regarded the Acts of Settlement and Uniformity of 1559 as a compromise. In fact, Elizabeth believed that faith was personal and did not wish, as Francis Bacon put it, to "make windows into men's hearts and secret thoughts". Elizabeth at the time took a stance of moderation where both Catholics and Protestants were allowed to freely embrace their beliefs on their own terms.There was little sense of favouritism towards either side. Of course, that was to change after the Battle of the Spanish Armada.

Further Division Between Protestants and Catholics

Though Elizabeth followed a largely defensive foreign policy, her reign raised England's status abroad. "She is only a woman, only mistress of half an island," marvelled Pope Sixtus V, "and yet she makes herself feared by Spain, by France, by the Empire, by all".Under Elizabeth, the nation gained a new self-confidence and sense of sovereignty, as Christendom fragmented.

Elizabeth was the first Tudor to recognise a monarch ruled by popular consent. She therefore always worked with parliament and advisers she could trust to tell her the truth—a style of government that her Stuart successors failed to follow. Some historians have called her lucky; she believed that God was protecting her.

The period after the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 brought new difficulties for Elizabeth that lasted until the end of her reign.The conflicts with Spain and in Ireland dragged on, the tax burden grew heavier, and the economy was hit by poor harvests and the cost of war. Prices rose and the standard of living fell.

In addition, relations between the papacy worsened. During this time, repression of Catholics intensified, and Elizabeth authorised commissions in 1591 to interrogate and monitor Catholic householders. This was mounted in the fear that the pope sought to reimpose religious authority and secular power over England. Like her father before her, the current pope excommunicated her, declaring her a heretic, dissolving Catholics’ duty of allegiance to her. This fear was further vindicated by the extended hostilities of the church and the invasion by Spanish forces. During the later period of the Elizabethan era, many Catholic Jesuit missionaries were prosecuted.

Catholic Persecution in the Late Elizabethan Era

To maintain the illusion of peace and prosperity, she increasingly relied on internal spies and propaganda. In her last years, mounting criticism reflected a decline in the public's affection for her.

One of the causes for this "second reign" of Elizabeth, as it is sometimes called, was the reshuffling of her main advisors. A new generation was in power. With the exception of William Cecil, most of her original ministers had passed: the Earl of Leicester in 1588; Francis Walsingham in 1590; and Christopher Hatton in 1591. Factional strife in the government, which largely remained restrained until the 1590s, was now rampant. A bitter rivalry arose between Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, and Robert Cecil, son of Lord Burghley, with both being supported by their respective associates. The struggle for the most powerful positions in the state marred the kingdom's politics. The queen's personal authority was lessening with age,as is shown in the 1594 affair of Dr. Lopez, her trusted physician. When he was wrongly accused by the Earl of Essex of treason out of personal pique, she could not prevent the doctor's execution.

Doctor Lopez is accused of poisoning Elizabeth I.

During the last years of her reign, Elizabeth came to rely on the granting of monopolies as a cost-free system of patronage, rather than asking Parliament for more subsidies in a time of war. The practice soon led to price-fixing, the enrichment of courtiers at the public's expense, and widespread resentment.

As Elizabeth aged, her image gradually changed. Well, when she was younger, most of her portraits retained an accurate depiction of her. But as she grew older, her painted portraits became less realistic and made her look much younger than she was. In fact, her skin had been scarred by smallpox in 1562, leaving her half bald and dependent on wigs and cosmetics. Her love of sweets and fear of dentists contributed to severe tooth decay and loss to such an extent that foreign ambassadors had a hard time understanding her speech. While it may be noted that Elizabeth was able to retain a slender figure well into her later years, her dental health was atrocious.

Portrait of elizabeth at younger age

Elizabeth’s make up being known as white clown face” at her old age

The more Elizabeth's beauty faded, the more her courtiers praised it. Elizabeth was happy to play the part, yet it is possible she may have grown disillusioned with it in her later life. Elizabeth was very indulgent with one of her favourites, Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex. He had been appointed to many important positions despite his growing record of irresponsibility and desertion. In addition, he took many liberties with Elizabeth, some of which could be considered outright disrespectful. Yet, despite all that, Elizabeth often forgave those slights.

Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex

After Essex's desertion of his command in Ireland in 1599, Elizabeth had him placed under house arrest and the following year deprived him of his monopolies. In February 1601, Essex tried to raise a rebellion in London. He intended to seize the queen but few rallied to his support, and he was beheaded on 25 February. The shock of having such a dear favourite betray her,as well as the guilt surrounding the decision to execute him, likely took a huge toll on Elizabeth. She was aware that she had given him too much leeway, which exacerbated his behaviour, culminating in his rebellion and resultant execution. She may have viewed herself as responsible for Robert Devereux's death, which likely worsened the guilt and mental turmoil she faced.

Execution of the Earl of Essex

Many historians of the 18th to the 20th century viewed her as a monarch who reigned over a bygone golden age. In reality, the Elizabethan era was not without its challenges.There were moments where Queen Elizabeth made.decisions that were hailed as decisive and other moments.where her.actions were criticised.. Yet, despite it all, the contributions she made vastly outweigh her less than desirable traits. She is still responsible for many of the contributions she made to the era, in part with the assistance of her many capable advisors. Her legacy is still one to be remembered and cherished, while addressing her flaws in a balanced light.

Protestant vs Catholic

Under the Anglican Church, the protestants still worshipped the same god but had a few fundamental religious beliefs that set them apart. This put the Protestants and Catholics at odds with each other, causing civil instability. It may have even been the catalyst for Catholic Mary I burning about three hundred Protestants at the stake during her five year reign of the country.

Protestants were often burnt at the stake for heresy

The Magisterium-The term “magisterium” refers to the official teaching body of the Roman Catholic Church. It's related to the large house of cardinals and the leading theologians in the movement; under the pope himself.”Besides providing a trusted, unified voice to guide Catholics, this body also allows the church to make official pronouncements on contemporary issues that the Scriptures might not directly address. There is no equivalent to the magisterium for Protestants.

Tradition--Protestants don’t view tradition as equal in authority with the Scriptures, only the Scriptures as authoritative, the Catholic teachings clearly state that the Church does not derive certainty about all revealed truths from the scriptures alone. Both scriptures and tradition must be accepted and honored with equal sentiments.

Salvation and Grace--Protestants often express the idea that salvation is by faith alone, through grace alone, in Christ alone. This assertion views justification as a specific point upon which God declares that you are righteous—a point where you enter into the Christian life. In contrast, the Roman Catholic Church views justification as a process, dependent on the grace you receive by participating in the Church—which is seen as a repository of saving grace.

Veneration of the Saints and the Virgin Mary---Roman Catholics see veneration, not as praying to the Saints and the Virgin Mary, but as praying through them. This is seen as similar to asking a brother or sister in Christ to pray for you. Dr. Svigel adds that departed saints are also “able to spill over their overabundance of grace to us.”Furthermore, Dr. Horrell notes that the Virgin Mary is seen as “the mother of our Lord, and therefore she is the mother of his body, and his body is the church, so she is the mother of the church. He is the creator of all things. So she is the mother of angels. She is the mother of humanity, as is sometimes said.”Moreover, the Catholic Church has also called her the Queen of Heaven. Historically, Mary was given a less prominent position in Protestantism as a reaction to this emphasis in the Catholic Church. There is no equivalent to this kind of veneration in Protestantism, as Protestants emphasise direct access to God.

The Virgin Mary

The State When Elizabeth Ascended

Furthering the Tudor conquest of Ireland, English colonists were settled in the Irish Midlands under Mary's reign. Queen's and King's Counties (now Counties Laois and Offaly) were founded, and their plantation began. Their principal towns were respectively named Maryborough and Philipstown.

Maryborough and Philipstown

While Henry VII had amassed a large amount of wealth for the crown Treasury through taxes and the issuing of large fines, most of it was spent by Henry VIII on opulent luxuries. In addition, the six years of Edward VI's reign over England were characterised by a series of poor harvests, meaning England lacked supplies and finances. In late 1557 convinced by her husband, Philip, Mary declared war on France, against the advice of her ministers and parliament. This ruined French trade with England as well as strained the relationship between England and the Papacy, which was allied with France at the time.

Henry VII, Founder of the Tudor Dynasty

While there was initial success with the war, the tide swiftly turned to worse as French forces took Calais, England's sole remaining possession on the European mainland. While the territory had been a financial burden on the English crown, its loss had been a mortifying blow to the Royal House. Perhaps due to the war against the pope's ally, France, Pope Pius V would soon come to excommunicate Elizabeth as well.

Siege of Calais

Philip II and Mary I

The weather during the years of Mary's reign was consistently wet. The persistent rain and flooding led to famine. Another problem was the decline of the Antwerp cloth trade. Despite Mary's marriage to Philip, England did not benefit from Spain's enormously lucrative trade with the New World. The mercantilist Spanish guarded their trade routes jealously, and Mary could not condone English smuggling or piracy against her husband. In an attempt to increase trade and rescue the English economy, Mary's counsellors continued Northumberland's policy of seeking out new commercial opportunities. While Mary had set the foundations for exploration, it had been Elizabeth, who ultimately brought English exploration to new heights.

In addition to poor international relations as well as England's poor finances, the most glaring problem was the civil instability brought about by two consequent Catholic and Protestant monarchs trying to restore the country to their desired religion. Edward’s aggressive reformation of the country to a Protestant one, as well as Mary's depraved burning of 300 Protestants had further divided the people of those two sects.

Persecution of Protestants under the Heresy Act

Edward VI sought to continue an agressive implementation

of the Reformation which his father began

Suitors

While Elizabeth was likely too young to comprehend the loss of her mother, she was certainly old enough to understand the execution of Catherine Howard. At age 8 or 9, she allegedly burst into longtime friend Robert Dudley’s arms, saying she never wanted to get married. What had happened just before that you ask?

Robert Dudley

Catherine Howard’s execution.

Catherine Howard had been executed shortly before that on 13 February 1542. She was only 18 years old.

Her father had been rather harsh to his six wives, changing them like tunics after each one outlived her purpose. In addition, Thomas Seymour’s harassment towards her despite residing in a seemingly happy marriage with Catherine Parr would have certainly taught Elizabeth about how love was prone to collapse under the temptation of power. As the Queen, anyone who married her would stand to gain a lot of it.

Seeing how these incidents from her childhood seem very likely to have affected the adult queen. It may well be that Elizabeth’s later decision not to marry was associated with this sexual harassment, at a pivotal period of her life. When she wrote “let him not touch me”, she prophesied not just about Thomas Seymour but about all the men she would encounter. As a result of Seymour’s actions, Elizabeth knew that when a man came a-courting, he would have one eye on her and one on the throne, and she was determined not to let any of them get their hands on it, or her.

In addition to personal experiences, there were also political reservations and a cultural basis surrounding Elizabeth’s decision to remain single.

In the 16th century, a sovereign was regarded as holding supreme dominion over the state, while a husband was deemed to hold supreme dominion over his wife. Elizabeth knew that marriage and motherhood would bring some erosion of her power, especially if she bore a son, which were more favoured than daughters. Politically, many of her citizens were opposed to her marrying a foreign monarch, especially a Catholic one. Marrying an English citizen would cause a power imbalance in her court. Her husband and his associates would stand to gain much power, causing jealousy to run rampant in her court. Factions would form, leading to further instability during her rule.

It is likely that she also feared childbirth. Two of her stepmothers, her grandmother and several acquaintances had died in childbirth. Moreover, in pregnancy, she was bound to lose her grip on affairs.

Elizabeth had to decide her priorities. There was no contraception in those days, and to risk an illicit pregnancy would have jeopardised her already insecure throne. A woman's reputation was paramount, especially that of a queen who bore the title Supreme Governor of the Church of England. Elizabeth was at the time of her ascension, declared a bastard by her father, Henry VIII. There were many who viewed her cousin, Mary, Queen of Scots, as a far more suitable candidate than her. Marriage or celibacy were her only choices. Elizabeth was far too intelligent to compromise herself.

Nonetheless, as a monarch herself, Elizabeth faced no shortage of suitors. The list included but was not limited to: King Eric XIV of Sweden, Archduke Charles of Austria, Francis Duke of Anjou, Robert Devereux, Phillip II of Spain, The Duke of Saxony, Adolphus, Duke of Holstein, Henry FitzAlan, 12th Earl of Arundel. All these were powerful men in their own rights. Hence, Elizabeth couldn't reject them too harshly, lest they turn their anger on England. Elizabeth had no intention of marrying any of these suitors, but still wanted to reap the benefits of maintaining an amicable relationship with them. She agreed to meet with potential spouses and dangled the possibility of marriage before them.

Henry FitzAlan, 12th Earl of Arundel

Erik XIV, King Of Sweden

Hence, she would leave them dangling for long periods of times, some were even left waiting for decades. They were left with the expectation that they would marry her, usually until they gave up or found another wife.

Partaking in marriage negotiations also enabled Elizabeth and her ministers to open up diplomatic channels with other kingdoms. The possibility of brokering a marriage alliance with Elizabeth also encouraged foreign leaders to act tactfully, rather than aggressively, in their policies toward England.

Elizabeth I wore her coronation ring as a sign of her symbolic marriage to the country. In 1603, she had gained some weight and had to have the ring sawed off. The ring, at that point, had cut into her finger and caused an infection. When the decision was made to saw off the ring, it sparked rumours among the superstitious Tudor society that her marriage to the country was over. These rumours came to fruition when she died just a few months later.

Representation of Elizabeth married with England

Notable Events

1558-Elizabeth I is crowned Queen

Elizabeth and the religious settlement

1559-Treaty of Cateau-Cambresis

This peace treaty between England and France ended the war inherited by Elizabeth from her half-sister Mary I, who went to war alongside her Spanish husband Philip II in 1557. Humiliatingly, Elizabeth had to confirm the loss of Calais, which had been an English possession since 1347.

Signage of the Treaty of Cateau-Cambresis

1560-Treaty of Edinburgh

1563-Statute of Artificers

1568-Genoese Loan

Italian bankers from Genoa had lent Philip II money to fund his campaign in the Netherlands (which was trying to put down the Dutch Revolt). Crucially, when the Spanish ships docked in English ports, the gold was seized by Elizabeth. This increased tension between England and Spain. Mary, Queen of Scots, flees from Scotland to England

1569-Revolt of the Northern Earls is crushed

1570-Pope Pius V excommunicates Elizabeth from the Catholic Church

1571-The Ridolfi Plot

1572-Vagabonds Act is passed

1574-Catholic priests are first smuggled into England

With the Pope’s blessing, foreign Catholic priests were smuggled into England with the sole purpose of continuing recusancy amongst the English Catholics and undermining the influence of Protestantism.

1576-Poor Relief Act is passed

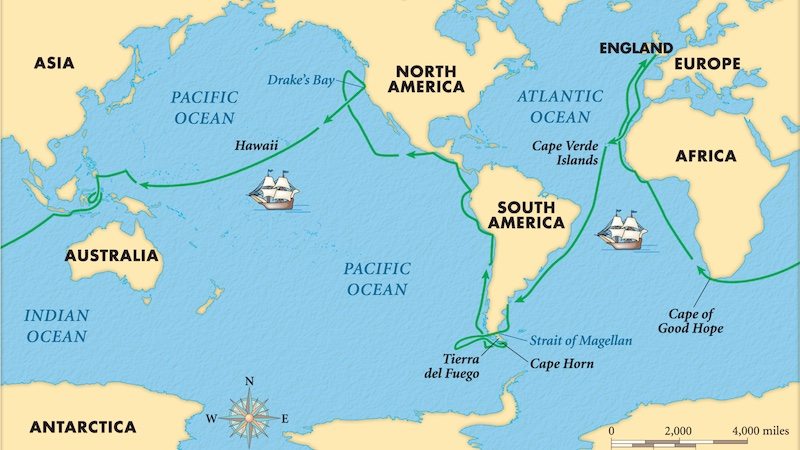

1577-80-Francis Drake circumnavigates the world

Drake was the first English person to achieve this (and the second person in history at the time). It was estimated that Drake returned with approximately £400,000 of Spanish treasure from regular raids of Spanish ports in South America.

1580-Francis Drake is knighted on the Golden Hind

This was an important symbolic gesture, which angered Philip II. He saw Drake as a pirate and therefore deemed Elizabeth’s act as deliberately provocative.

The Golden Hind and the dread pirate Sir Francis Drake

Contemporary Depiction of the Golden Hind

1583-The Throckmorton Plot

1584-Treaty of Joinville

The French Catholic League signed this treaty with Philip II of Spain. The aim was to rid France of heresy (Protestantism). This meant two of the most powerful European nations were now united against Protestantism, placing Elizabeth in a precarious position.

1585

Treaty of Nonsuch

This significantly committed Elizabeth to support the Dutch rebels directly against the Spanish. She pledged to finance an army of 7,400 English troops and placed Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, in charge of them. Essentially, this meant England and Spain were now at war.

All Catholic priests are ordered to leave the country

With the seemingly imminent war between Spain only a matter of time, Elizabeth was determined to rid England of the ‘enemy within’. Catholic priests were ordered to leave so as not to influence the English Catholics with divided loyalties.

First English colony in Virginia established

This was viewed as significant because it was seen as a means to increase trade, to expand Protestantism and to use the area as a base for attacks on Spanish colonies in the New World. In this sense, the colonisation of Virginia should be understood in relation to the wider conflict with Spain.

1586-Babington Plot

Treaty of Berwick

Elizabeth and James VI agreed to maintain Protestantism as their respective countries’ religion. James also pledged to help Elizabeth if invaded. The treaty essentially allowed Elizabeth to focus on developing events in the Netherlands and not worry about protecting her northern border.

Surviving colonists abandon Virginia and return to England

The failure of the colonisation was due to: the resistance of the Native Americans; conflict amongst the English settlers (who collectively had the wrong mix of skills to make the settlement a real success); the loss of supplies via the damage incurred on The Tiger and the fact that the voyage set off too late for crops to be planted (causing dependence on the rightfully suspicious Native Americans).

1587-Mary, Queen of Scots, is executed

Babington and other known plotters were hanged, drawn and quartered.

Colony is established at Roanoke

Despite the failure of 1585, another attempt to colonise Virginia took place. Many colonists this time were poverty-stricken Londoners (it was felt they would be used to hard work and would therefore be happy to work for a new life in the New World). Working for the British, Native American Manteo was placed in charge of the expedition by Sir Walter Raleigh. Native American hostility occurred from the start, however. John White (another leading colonist) sailed back to England to report on the problems being experienced.

The ‘singeing of the King’s beard’

Francis Drake led an attack at Cadiz on the Spanish fleet, who were preparing for an invasion of the English. The attack was a success. 30 ships were destroyed, as well as lots of supplies. This delayed the Spanish attack and gave the English more time to prepare (hence the attempted invasion of the Armada one year later in 1588).

An attack on supply lines that ended in the delay of the Spanish invasion by a year

1588-Battle Of the Spanish Armada. England Wins.

1590-English sailors land at Roanoke to find it abandoned

1603-Death of Elizabeth I

Ruling

Despite Elizabeth stating in her speech before facing the Spanish Armada that she was a weak and feeble woman, she was known for her volatile temper, which she inherited from both her father and mother.

Elizabeth was known as a witty, kind woman but her temper could really flare up. Despite remaining regal at times, she could occasionally burst into acts of violence against her own courtiers.

Her godson, Sir John Harington, wrote of her temper, saying, “When she smiled, it was a pure sunshine that every one did choose to bask in; but anon came a storm from a sudden gathering of clouds, and the thunder fell, in wondrous manner, on all alike.”

In an article on his biography of Elizabeth I, historian John Guy wrote, “She was vain and courted flattery; she was jealous of her younger maids’ youth and beauty. She had a vicious temper, attacking one of them with her fists and breaking the girl’s finger. And she could swear volubly. Only the foolhardy approached her if she was in a foul mood.

No one was safe, not even her closest advisors. Elizabeth allegedly kicked and punched her personal secretary, William Davison. We can see further proof of her temper when Mary I commissioned an atlas in 1558 from the Portuguese mapmaker Diego Homen as a gift for her husband Philip II of Spain. Mary died before the atlas was finished, and after her death, the atlas was presented to Elizabeth I, Mary’s successor to the English throne. The right side of the heraldic shield on the map shows Mary’s coat-of-arms: lions quartering the fleurs-de-lis. Philip’s coat-of-arms, on the left, has been scratched out. The sight of the arms of Catholic Spain emblazoned over England would have infuriated the new Protestant queen. It was well known that Elizabeth had a terrible temper, and she despised Philip. This may well have led her to scrape Philip’s coat of arms off the map. In 1598, an angry Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, quite forgot himself and turned his back on the queen. Elizabeth’s response to this rudeness was to hit him on the side of his head and then “she bade him get him gone and be hang’d.” Unfortunately, the earl then put his hand on his sword, and the Lord Admiral had to step between the queen and her favourite to diffuse the situation.

Philip's Coat of Arms (Over England) is Missing

Elizabeth especially hated receiving bad news. In March 1586, Elizabeth threw a slipper at Sir Francis Walsingham, her secretary and spymaster, after finding out from the master of a ship that had just arrived from Spain that he’d seen 27 Spanish galleons gathered at Lisbon, describing them as “floating fortresses. Walsingham had downplayed the threat and Elizabeth was livid. Ambassador Mendoza recorded her anger: “When the Queen heard this she turned to Secretary Walsingham, who was present, and said a few words to him which the shipmaster did not understand ; after which she threw a slipper at Walsingham and hit him in the face, which is not a very extraordinary thing for her to do, as she is constantly behaving in such a rude manner as this.”

Yet, despite her violent temper, she could also be kind and generous. She fed Burghley with broth as he lay dying. She wrote gentle, consoling letters in her neatest writing to bereaved courtiers or their wives.”

Lord Burleghley(left), Queen Elizabeth I (middle), Francis Walsingham (right)

Close Advisors and Friends

Elizabeth had a few ladies in waiting, all of whom maintained unyielding loyalty to her, only leaving her service when they passed or when her temper got the best of her. Chief of her ladies in waiting was Kat Ashley and Blanche Perry. In addition, she had many capable advisers which proved the foundation of her reign. With them by her side, she was able to efficiently implement internal policies and they were integral in maintaining her safety by pressuring her to make the right decisions no matter how hard they may have been. This was further proven in the execution of Mary of Scots, despite how apparently reluctant Elizabeth was when going through with it.

Despite Elizabeth's frequent temper tantrums with some of her courtiers, she likely appreciated their services. This is proven in her assigning of affectionate nicknames to some of her favourites. Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, was nicknamed her eyes. William Cecil, her chief adviser, was nicknamed her spirit. Robert Cecil, his son, who was small and hunched back, was nicknamed her “elf ” or “pygmy". In perhaps the most unusual turn, she nicknamed her spymaster, Frances Walsingham, her moor.

Kat Ashley

KAT ASHLEY

The woman who loved Queen Elizabeth I as a daughter.

Ashley initially served as Elizabeth’s childhood governess, teaching her the basics of etiquette and the necessary aristocratic skills. She also taught Elizabeth academic subjects such as mathematics, geography, astronomy, history, French, Italian, Flemish and Spanish. Elizabeth herself praised Kat’s devotion to her studies by stating that she “took great labour and pain in bringing of me up in learning and honesty.”

In 1545 Katherine married John Ashley, Elizabeth’s senior gentleman attendant and a cousin of Anne Boleyn. She was over 40 years old at the time. Even as Elizabeth progressed to tutors who could give her more advanced education, Ashley still remained close by Elizabeth's side.

After the Seymour scandal had blown over, Katherine was allowed to rejoin Elizabeth until the latter’s imprisonment in wake of the Wyatt rebellion. Then in May 1555, she was arrested over the discovery of books inciting rebellion.

She was found innocent after spending three months in prison, but was forbidden to see Elizabeth after her release. Upon Elizabeth's ascension to the throne, Catherine was granted control over Elizabeth's household while her husband was made to manage the crown jewels.

Kat soon became very influential as a source of information for the queen. She helped form a strict aristocracy, which helped maintain Elizabeth's hold over government for most of her reign.

Elizabeth was known to be very affectionate with Katherine. In May 1561 she gave Katherine a velvet gown. Catherine peacefully died in 1565 at the ripe age of sixty three to Elizabeth's distress. Elizabeth was not in attendance in court when Ashley passed, likely accompanying the latter on her deathbed. Elizabeth was known to continuously visit her and mourned her death sincerely.

Blanche Parry

BLANCHE PARRY

Blanche was Elizabeth's former cradle rocker and had remained her close attendant up until Elizabeth's coronation as queen. After Ashley's death, she succeeded her as Chief Gentlewoman of the Privy Chamber and was one of those who controlled access to the queen. Blanche also remained in control of the Queen's jewels from before her accession, the great seal of England for two years and also managed many of the Queen's personal possessions. Her duties included receiving considerable sums of money on behalf of the queen, passing information from the queen in vital times. She received presentations of parliamentary bills for the queen, wrote letters on the Queen's behalf. She also supervised the Queen's linen and other things which may have included a pet ferret.

Like Ashley before her, Blanche held a position at the centre of the court. Having the ability to make pleas on behalf of those suffering under royal displeasure, this helped to quell civilian resentment, maintaining the Crown’s stable hold over politics. She was friends with her cousin Sir William Cecil, the Queen's chief advisor and worked closely with him.

Elizabeth placed a large amount of trust in Blanche and bestowed upon her many material awards, including two wardships, acquired lands in Herefordshire, Yorkshire and Wales. The Queen also frequently gifted her used items of clothing.

This relationship was reciprocal as Blanche gave Elizabeth presents of silver, including a double porringer and four silver boxes. On New Year's Day, 1572 she gave the Queen a flower of gold enamelled with rubies and diamonds, which the queen later gave to another confidant, Elizabeth Howard. In 1573, Blanche gave Elizabeth a jewel of mother-of-Pearl set with gold pendant. In 1575, Elizabeth received a gold flower with three right roses with enamelled ruby and in the midst, a carved fly.

Porringer

In 1587, at the age of 79, likely due to her advanced age, responsibility for the Queen's personal jewellery was now passed to Mary Radcliffe. Before passing over her duties to Mary, Blanche made an inventory of the jewels, listing 628 pieces delivered into the custody of Radcliffe.

William Cecil supervised both of her wills, the first in 1578, and her final will which was dated in 1589. Blanche was one of Elizabeth's longest serving attendants. When she passed at the age of 82 on February 12th 1590, she did so with the rank of Baroness and the queen having paid all of her funeral expenses.

Francis Walsingham

FRANCIS WALSINGHAM

Walsingham entered King's College for his university education with many other Protestants, but did not sit for a degree. Upon Mary I’s accession to the throne, many wealthy Protestants fled England, Walsingham among them. He studied law at the University of Padua in Italy and the University of Basel in Switzerland. Walsingham returned to England upon Mary’s succession by Elizabeth, Through the support of one of his fellow former exiles, the 2nd Earl of Bedford, he was elected to Elizabeth's 1st parliament as the member for Bossiney, Cornwall in 1559.

By 1569, Walsingham was already working with William Cecil to counteract plots against Elizabeth. Walsingham was instrumental in the collapse of the Rudolphi plot, which aimed to replace Elizabeth with Mary of Scots. He was also Elizabeth's propaganda minister, decrying a conspiratorial marriage between Mary and Thomas Howard. He soon interrogated the main conspirators of the Ridolfi plot at his house. In 1570, Elizabeth chose Walsingham to support the Huguenots in their negotiations with Charles of France. He soon succeeded Sir Henry Norris as the English ambassador in Paris. One of his duties was to continue negotiations for a marriage between Elizabeth and Henry, Duke of Anjou. The marriage plan was eventually dropped as Henry was a Catholic. A substitute match was proposed but that fell through as well . Walsingham believed it would serve England better to seek a military alliance with France instead.

When Catholic opposition in France resorted to the death of Huguenot leaders, Jean of Navarre and Gaspard De Coligny, culminating in the St Bartholomew's Day massacre, Walsingham's house in Paris became a temporary century for Protestant refugees. His wife, who was pregnant, escaped to England with their 4 year old daughter, giving birth to a second girl in January 1573 while Walsingham was still in France. In April 1573 he returned to England, having established himself as a trusted official of the Queen and Cecil.

In December that year, he was appointed to the Privy Council of England and made joint principal secretary with Sir Thomas Smith. The latter would retire in 1576, leaving Wolsingham in effective control of this position. He would be knighted on the first of December 1577, holding multiple posts in the aristocracy.

The duties of principal secretary were never formally defined, but Walsingham handled all royal correspondence and determined the agenda of council meetings. This caused him to wield great influence in most methods of policy as well as in foreign and domestic fields of government. Alongside Cecil, he supported most of England foreign trade policies with neighbouring European states.as well as Sir Francis Drake's expeditions abroad. Walsingham also advocated for direct intervention in the Netherlands in support of the Protestant revolt against Spain. Cecil, on the other hand, was more open to a policy of mediation, one that Elizabeth endorsed. In 1578, Walsingham was sent on an embassy to the Netherlands to sound a potential peace deal and gather military intelligence.

When France proposed to renew the marriage alliance with England, Walsingham publicly opposed the marriage, perhaps to the point of calling an uprising against it. He compared the match with the one that occurred the week before the St Bartholomew's massacre, calling it the most horrible spectacle he had ever witnessed. He implied religious riots would break out if the marriage proceeded. Elizabeth was often thankful for his blunt, often unwelcome advice, knowing the advice was given with the best interests of the crown at heart. There was a letter in which Elizabeth acknowledged his strong beliefs, calling him her Moor who cannot change his colour. This was likely Elizabeth making fun of his habit of often dressing in sombre, dark clothes. A moor is a patch of black water and by calling Wolsingham a moor who cannot change his colour, this was likely a reference to his unshakable beliefs.

He did not like the nickname, as he usually smiled in unamusement when he was addressed as such by Elizabeth.

Walsingham was also the victim of Elizabeth’s fits of violence. Yet despite all this, he maintained a high level of trustworthiness and loyalty to the crown, allowing him to develop a vast network of spies and informants, acquiring intelligence and statistics which he would use to infiltrate Catholic conspiracy circles. He had created a professional Secret Service, often resorting to the use of double agents and prison informants. Walsingham's spy network would prove invaluable on multiple instances, including the execution of Mary of Scots, as well as the preparation for English combat against the Spanish Armada. Notably, he, along with William Cecil, called for the execution of Mary of Scots as well as formulated the plan to entrap her of plotting to assassinate Elizabeth. Elizabeth was undoubtedly upset by the premature proceeding of Mary's execution. He did not have to suffer from much of it as he was absent from court, ill at home in the weeks spanning the execution.

In addition to derailing the Throckmorton and the Ridolfi plots, as well as other threats to Queen Elizabeth's life, he received many dispatches from his agents in mercantile communities and foreign courts detailing Spanish preparations for an invasion of England. His recruitment of Anthony Standen, a friend of an ambassador to Madrid gave extremely revealing statements. Walsingham worked hard to prepare England for war with Spain particularly by supervising the substantial rebuilding of Dover harbour and encouraging a more aggressive strategy. On his orders, the English ambassador in Turkey made an unsuccessful attempt to persuade the Ottoman Sultan to attack Spanish forces in the Mediterranean. Walsingham also supported Francis Drake's attack on Spanish ships which wreaked havoc on their logistics. When the Spanish Armada sailed for England in July 1588, he received regular dispatches from the English Naval Forces and raised his own troop of 260 men as part of the land defences. On 18th August 1588, after the dispersal of the Armada, the Naval Commander Lord Henry Seymour, wrote to Walsingham, “You have fought more with your pen than many have in our English Navy fought with their enemies.”

In terms of foreign intelligence, Walshingham’s extensive network spanned Europe and the Mediterranean. While foreign intelligence was a normal part of the principal secretary's activities, he cast his net more widely than his predecessors, exploiting links across the continent to ensure the Crown’s safety.

Starting from 1571, Walsingham often complained of ill health and retired to his estate for recovery. Overtime, his health slowly deteriorated and he died on 6 April 1590 at his house. He was 58 years old.

While Walsingham had received many grants of land from the queen, grants for the export of cloth and the leases of custom, as well as owning multiple residences, he spent much of his own money on espionage in the service of the queen. This only further highlights his loyalty to the crown, and in the end, he died Her Majesty's loyal servant. Unfortunately, unlike William Cecil, most of his personal character remains elusive. His private papers were lost while most of his public ones were seized by the government. The fragments that do survive to the modern day demonstrate his personal interest in gardening and falconry.

William Cecil

WILLIAM CECIL

William Cecil was Elizabeth’s right hand man and closest advisor during her reign.

He went to St John's College, but he was brought into contact with Roger Ascham and John Cheke, acquiring an unusual knowledge of Greek. Against his family's wishes, he married Cheke's sister, Mary, and was removed from University. They were married in 1541 but Mary died tragically, in February 1543. On 21st December 1546, he married again to Mildred Cooke, ranked by Ascham as one of the most learned ladies in the kingdom.

His early career was spent in the service of the Duke of Somerset, Lord Protector of Young Edward VI. Cecil seemed to have been the private secretary of the protector. He was in some danger when Somerset was executed, as Cecil landed imprisoned in the Tower of London.

He associated himself with John Dudley, then Earl of Warwick. On 5th September 1550, he was sworn in as one of King Edwards' two secretaries of state. To prevent either Mary and Elizabeth from succeeding Edward, Northumberland forced King Edward's lawyers to create a device setting aside the third succession act on 15 June 1553. Cecil resisted for a while. In a letter to his wife, he wrote that he did not want to.go through with it. However, in the end, he ended up signing the device.

As the tide eventually shifted in Mary I's favour, Cecil switched sides immediately and later gave a full account of the events before her. It is to this event he owes his immunity. He had moreover, no part in the divorce of Catherine of Aragon or the humiliation of Mary during Henry VIII's reign. Cecil immediately conformed to the Catholic regime despite being a Protestant himself. It was thanks to this that he was able to live quietly during Mary's prosecution of Protestants.

The Duke of Northumberland had once employed Cecil in administering Princess Elizabeth's lands. Before Mary died, he was part of Elizabeth's close tight knit circle. When she ascended the throne, she soon came to rely on him. He was the cousin of Blanche Perry, Elizabeth's close confidant. His tight control over the crown's finances, leadership of the Privy council and the creation of the intelligence service under the direction of Francis Walsingham would make him one of the most influential ministers in the Elizabethan era.

In his foreign policy, Sessel's long-term goal was a united and Protestant British Isles, an object.to be achieved by completing the conquest of Ireland and creating an Anglo Scottish Alliance. With the.land border with Scotland safe, the burden of defence would fall upon the Royal Navy. Hence, Cecil proposed to strengthen the Navy, making it the centerpiece of English power. He did obtain a firm alliance with the other powers on the British Isles. Unfortunately, some parts of his strategy ultimately failed as a united British Isles becoming the axiom of English policy would not come to fruition until the 17th century.

Though he was Protestant, Cecil was not a purist as he aided Protestant efforts abroad just enough to keep them going in the struggles that danger was kept away from England shores. However, he could be proven to strike hard when necessary, and his action over the execution of Mary Queen of Scots proved he was willing to take on responsibilities from which the queen shrank. In terms of domestic policy, it is likely that Cecil had some influence on the national laws that Elizabeth passed.

Cecil had a considerable share in the religious settlement of 1559 as it coincided fairly with his own religious views.The nation. He grew more Protestant as time wore on. and he was happier to persecute Catholics, which likely led to negative propaganda of his being widespread.

In terms of commercial policy, he sought to ensure the crown had an abundance of resources, leading him to advocating a cautious policy. These economic ideas were influenced by the advisors of Edward’s reign. He believed in the necessity of safeguarding the social hierarchy, the just price and moral duties due to labour. His economic policy was also motivated by national independence, self sufficiency and the balancing of the interests of the crown and the subject. He believed that economics and politics were interlinked. One could easily affect the other. He deplored the reliance on foreign money and during an economic depression, sought to ensure employment due to fear of revolts. Cecil also used patronage to ensure the nobility's loyalty to the crown.

On 25th February 1571, Queen Elizabeth elevated him to Baron Burghley. Cecil continued to act as secretary of state after his elevation, illustrating the growing importance of the post. In 1572 Cecil privately admonished Elizabeth for her alleged leniency with Mary. Cecil was always willing to make a strong attack on everything he thought Elizabeth had done wrong as queen. He viewed that Mary had to be executed because she had become a rallying cause for Catholics, Spain and the pope to dethrone Elizabeth. Elizabeth's indecision regarding Mary's treatment was frustrating and finally, in 1587, he persuaded Elizabeth to have Mary executed.

In 1598 Cecil collapsed, possibly from a stroke or heart attack. He died at his London residence on the 4th of August 1598, aged 77. His only surviving son Robert was ready to step into his shoes as the Queen's principal advisor.

William Cecil's private life was upright. He was a faithful husband, a careful father and a dutiful master.He decided to Chronicle 128 letters to his youngest son, Robert over the course of his life. In those letters, he left words of guidance and perseverance to his son. This collection of letters was the largest collection of paper showing the close direction and counsel he gave his son in seeking and obtaining the office of Principal Secretary from 1593 to 1598. These materials concentrated on receiving and crafting a large variety of papers on behalf of Elizabeth and her Privy Council from the aspects of finance, administration, foreign policy and religion. These letters reflect Cecil's care for his family, his thoughts of death and a unique record of illness and old age framed by his political and spiritual anxieties for the future of the queen after his passing.

Like Walsingham, he was loyal to the queen until the end.

Francis Drake

FRANCIS DRAKE

Francis Drake initially started out as a small trader until he took part in John Hawkins’ pursuit of the slave trade in the 1560s. During a particular rate, the ship was under fire by Spanish hostility, armed conflict.and returned home after dangerous circumstances. While it was still negotiating to resupply and repair, the ships were again attacked by Spanish forces. Abandoning the majority of the crew, Francis made it back to England with just 15 men. He abandoned hundreds. After arriving back in England, Hawkins accused Drake of desertion and stealing the treasure they had accumulated. Drake denied both accusations, asserting he had distributed all profits among the crew and he had believed Hawkins had perished upon his departure. This is believed to have been when Drake's hostility towards the Spanish started and he would, for the rest of his life, dedicate himself to attacking Spanish possessions whenever he found them.

Drake's first raid on the Spanish was in 1572, off the coast of Panama where gold and silver was brought for over from Peru and to be transported to the Caribbean Sea, where Spanish Galleons would take it abroad to their towns. Unfortunately, he was heavily wounded when the Spanish arrived from Panama and he had to have his forces retreat without the treasure. Rather than attacking them at the intersection point again, he raided the Spanish ships along the coast and with enslaved Africans who had escaped from their Spanish slave owners, managed to successfully loot the treasure from Panama City. One of those slaves eventually became a free man after years of service under Drake. Unfortunately, there was too much treasure for them to bring home and they buried much of it, taking only gold back with them. Their fortunes turned for the worst when their boats disappeared by the time they had gotten to the coast. The Spanish were hot on their heels but ultimately, Drake had managed to return to England with a small amount of gold.

He was involved in a defensive position during the Rafflin Island massacre of Ireland.

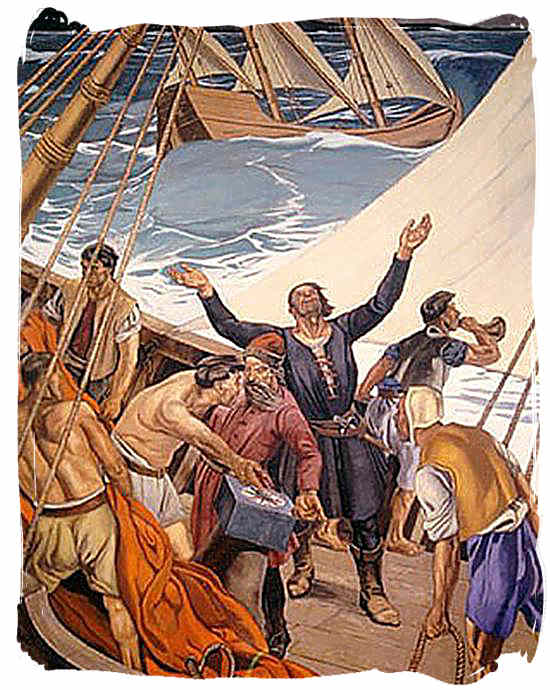

In 1577, fired by accounts of fortunes to be made in foreign lands, he set out to circumnavigate the earth. His route lay south-west across the Atlantic, round the Cape Horn by the channel that Magellan had pioneered, then up the west coast of South America, pausing from time to time to sack a Spanish town or capture a Spanish treasure ship. Perhaps still searching for that elusive north-west passage, he sailed up the coast of North America, until at about the latitude of [modern] Los Angeles he changed course, to catch the trade winds west across the Pacific, towards the Spice Islands, pausing there to recondition his ship and load a precious cargo of cloves. Then he headed across the Indian Ocean, round the Cape of Good Hope, up the coast of Africa and home. He had begun with five ships. Even by the time he reached the Magellan Straits he was reduced to only one ship, which he renamed the Golden Hind, and his crew was riddled with scurvy and mutiny. With her gift for public relations, the Queen knighted him on the deck of the Golden Hind when he returned in 1581. Other nations, particularly the Portuguese, had circumnavigated the world before him, but Drake’s achievement – in his tiny, indomitable ship, only 70 feet long and 19 feet wide – was still astounding.

After his circumnavigation across the globe, Francis continued persistently raiding ships on the Spanish American West Coast. Now under imperial funding, most of these expeditions were now successful as he brought back mountains of gold and treasure back to the English crown.

In addition to pirating, Drake was also an explorer, as he passed the Baja Peninsula and continued north to the western coast of North America. The ship made first landfall just south of modern Oregon, then sailed southward. On 17 June, he and his crew found a protected cove when they landed on the coast of what is now Northern California. While ashore, he claimed the area for Queen Elizabeth as New Albion. Soon after he had friendly interactions with some of the natives and explored the surrounding land by foot. When a ship was ready for the return voyage, they passed the journey the next day when anchoring the ship at the Farallon Islands where they hunted sea lions or seals.

His journey also took him to a group of islands in eastern modern day Indonesia. Of course, considering winds and currents at the time, it is more likely he careerd his ship on the shore of Magdalena Bay in lower California and sailed to the Malaccas and Spice Islands from there. He befriended a local Sultan in the area and became involved with some intrigues with the Portuguese in that region.He made multiple stops on his way towards the tip of Africa, eventually rounded the Cape of Good Hope and reached Sierra Leone by 22nd July 1580.

Cape of Good Hope history, with Vasco da Gama and Bartolomeu Dias

When he returned from his circumnavigation around the globe on 26th September 1580, he sailed into Plymouth with fifty nine remaining crew on board, along with a rich cargo of spices and captured Spanish treasures. The Queen's share of the cargo surpassed her income for the entire year. She declared that all written accounts of Drake's voyages were to become the Queen's secrets of the realm with the intention to keep his activities hidden from the eyes of Spain.

Francis made an expedition to America where he set up a small colony, but his finest hour was during the attack with the Spanish Armada. In 1587, he accepted a new commission with several purposes: to disrupt Spanish shipping routes, to trouble fleets that were in their home ports and to capture Spanish ships laden with treasure. He was also told to attack the Spanish Armada had it already sailed for England. When he arrived in Spain's major port on 19th April 1587, he found a harbour packed with ships and supplies. The Armada was ready, waiting for a fair wind to send them to England. The next day, Drake attacked the Inner harbour and inflicted heavy damage. Regardless, Drake had sunk around 24 ships, and his attack became known as the singeing of the king's beard. This delayed the Spanish invasion by a year as they had to recover their losses. Over the next month, Drake will also continue to destroy ships on the Spanish supply lines.

When the Spanish Armada set sail for England in May 1588, they arrived on the English coast near Cornwall on 29th July. The English Navy, under the command of Lord Howard of Effingham and Sir Francis Drake serving as Vice Admiral, commanded the Galleon Revenge. Greek would proceed to capture a disabled Spanish galleon, along with the commanding officer and the rest of his crew. This ship in particular was known to be carrying enough funds to pay the Spanish armada.

Surprisingly, Philip appointed the Duke of Medina Sidonia, a man with complete lack of military experience to command the Armada. The Duke made his way up the Chanel towards the French shore with his flagship, thinking if he anchored in French waters, the English would dare not attack. The English launched eight fire ships into the midst of the Armada, forcing its captains to sail into the open sea. Decisive action was fought the next day, where the English Navy pounded the Spanish ships with their guns. Five Spanish ships were lost. The Armada having failed, were unable to sail back via the English Channel. The English ships, including Revenge, pursued them to prevent them from making a landing on English soil. Eventually, after heavy battle, the fleet moved back to Spanish ports, having lost almost half their original number.

Unfortunately, after the Spanish Armada, Francis had a number of failed expeditions, which thankfully, did not have too much of a loss. On 28 January 1596. Drake died of dysentery, a common disease in the tropics, while on another raid of the Spanish treasure ships. Following his death, the English fleet withdrew defeated.

Circumnavigation of Francis Drake

Internal Contributions

Wool trade

A 1571 Act of Parliament to stimulate domestic wool consumption and general trade decreed that on Sundays and holidays, all males over six years of age, except for the nobility and persons of degree, were to wear woollen caps on pain of a fine of three farthings (¾ penny) per day. This law instituted the flat cap as part of English wear. At the time wool was subject to taxes.This law would further increase the demand for production of wool, and thereby increasing the tax revenue from wool. The 1571 act was repealed in 1597.

The Arts

While Elizabeth rarely offered personal patronage to artists, she likely created a demand for the industry as well as creating an environment where artistic pursuits could be pursued without restriction by religion.

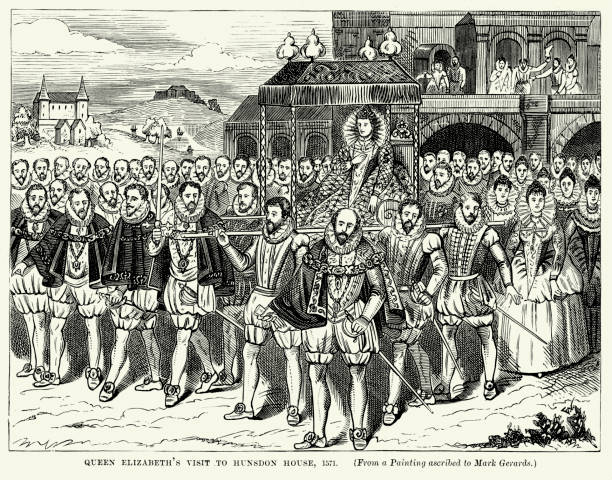

In Elizabeth's reign architecture took on a new importance as the growing class of wealthy courtiers began to build huge homes called "great houses" or "prodigy houses" in rural areas of England. Most summers Elizabeth took trips called progresses around the English countryside, usually travelling with a retinue, or group of attendants, of about five hundred people. She and her full retinue lodged at the great houses of her courtiers, and the hosts were expected to feed, house, and entertain this huge group of guests. Though the queen's visits were extremely expensive, they were considered a great honor to the host. Competition grew among courtiers to build bigger and more elaborate country estates.

A manor designed common to the upper class

In the cities of Elizabethan England, another common style of house evolved for merchants and the growing middle class. The exterior of the house was black and white with dark wood beams and white clay walls. The bottom floor of the city home was usually a shop or place of business, while the upper floors, which overhung the lower floors and had more room, were the living quarters for the family.

Merchant House

Elizabeth was an accomplished musician, playing the lute and the virginal (a small, legless, rectangular keyboard instrument related to the harpsichord) as well as composing her own music. As queen, Elizabeth supported music of all kinds, from popular songs to church music. She kept about seventy musicians in the royal court, and she expected her courtiers to sing, play musical instruments, and dance with grace and ability.

National Religion

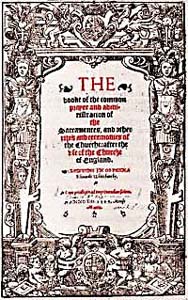

In this period, Elizabeth managed to moderate and quell the intense religious passions of the time. This was in significant contrast to previous and succeeding eras of marked religious violence. This was mostly accomplished by passing the Act of Supremacy, the Act of Uniformity, as well as reintroducing the prayer book from her brother's reign.

Soon, the Anglicans started to define their Church as a middle ground between the religious extremes of Catholicism and Protestantism; Arminianism and Calvinism; and high church and low church.

Reformation bill

When the Queen's first Parliament opened in January 1559, its chief goal was the difficult task of reaching a religious settlement. There were many different schools of thought, all of which wanted different things. Thankfully, after much discussion, it was decided that the Ordinal and Prayer Book provisions were removed and the Mass left unchanged, with the exception of allowing communion under both religions. The Pope's authority was removed, but rather than granting the Queen the title of Supreme Head, it merely said she could adopt it herself. This bill would have returned the Church to its position at the death of Henry VIII rather than to that when Edward VI died. It was a defeat for the Queen's legislative programme, so she withheld royal assent.

Act of Supremacy

Following the Queen's failure to grant approval to the previous bill, Parliament reconvened in April 1559. At this point, the Privy Council introduced two new bills, one concerning royal supremacy and the other about a Protestant liturgy. The Council hoped that by separating them at least the Supremacy bill would pass. Under this bill, the Pope's jurisdiction in England was once again abolished, and Elizabeth was to be supreme governor of the Church of England instead of supreme head. All clergy and royal office-holders would be required to swear an Oath of Supremacy.

The alternative title was less offensive to Catholic members of Parliament, but this was unlikely to have been the only reason for the alteration. It was also a concession to the Queen's Protestant supporters who objected to "supreme head" on theological grounds and who had concerns about a female leading the Church.

The bill included permission to receive communion in two kinds. It also repealed the heresy laws that Mary I had revived. The heresy laws would allow the monarch to deal with religious dissenters however necessary. Catholics gained an important concession as they would be free to practice their religion. Under the bill, only opinions contrary to Scripture, the General Councils of the early church, and any future Parliament could be treated as heresy by the Crown's ecclesiastical commissioners. While broad and ambiguous, this provision was meant to reassure Catholics that they would have some protection.

The bill easily passed the House of Commons. In the House of Lords, all the bishops voted against it, but they were joined by only one lay peer. The Act of Supremacy became law.

Act of Uniformity and prayer book

Another bill introduced to the same Parliament with the intent to return Protestant practices to legal dominance was the Uniformity bill, which sought to restore the 1552 prayer book as the official liturgy. The Act of Uniformity required church attendance on Sundays and holy days and imposed fines for each day absent. It authorized the 1559 prayer book, which effectively restored the 1552 prayer book with some modifications. The Litany in the 1552 book had denounced "the bishop of Rome, and all his detestable enormities".The revised Book of Common Prayer removed this denunciation of the Pope.

To enforce her religious policies, Queen Elizabeth needed bishops willing to cooperate. Hence, a number of new bishops were consecrated from December 1559 to early 1560.

Book of Common Prayer, 1549

Postal Service

Many Tudor guilds and universities had their own private postal services at the time. Sofia of spice, sending out messages of the country via private mail. The government insisted a Master of Posts be elected to carry all letters sent outside of England. This was to ensure they could read any suspicious letters and potentially thwart any plots to endanger the country's stability.

Commerce

Aid Laws

1563: Statute of Artificers:

This had the central aim of making poor relief more effective. Anyone who refused to pay into the poor relief could be sent to prison and in those towns were poor relief was collected poorly the officials would be fined £20, which is equivalent to £5000 today.

1572 Vagabonds Act:

The Vagabonds Act wanted to end the problem of vagrancy in England. It created harsh punishments such as whipping, holes being drilled in ears, prison and even death. However, it also started to tackle unemployment. The act created a register of the poor in each local area, made towns and cities responsible for finding jobs for those idle poor and created a national poor rate.

1576 Poor Relief Act

This act wanted to differentiate between those idle poor and those who were impotent. It made Justices of the Peace provide raw materials for the able bodied poor to make things that they could sell as a business to make money. Raw materials included things like wood, straw and wool. Houses of Correction were also set up where those who refused to work were also sent.

Correction House to give work to those who were idle

Poor Law 1601

This law sought to consolidate all previous legislative provisions for the relief of 'the poor'. The Poor Law made it compulsory for parishes to levy a 'poor rate' to fund public assistance for those who could not work.

Currency Reform

When Queen Elizabeth I came to power, she inherited one of the most debased coinages in history, which damaged trade relations and the reputation of the monarchy. Elizabeth’s father, Henry VIII, had authorised a series of debasements which meant that in the space of just seven years the silver content of English coins was reduced by more than 80%. Counterfeiting was rife, with contemporary reports claiming that a great multitude of false money was in circulation.

The status of the country’s coinage reflected its reputation on the international stage and the authority and competence of its government. Debasement of the coins in circulation wreaked havoc in the marketplace: at one time the shilling, the original value of which was 12d, was worth half its value at 6d and at its lowest point traded for just 2¼d, less than a fifth of its actual value.

Coins were commonly used during the Elizabethan era

Bank notes only came into use in 1694, during the rule of the Stuart era.

For ordinary people, fluctuating values had serious consequences. Prices rose because sellers anticipated a drop in value and adjusted their prices accordingly. The reputation of English coins was so badly damaged that on occasion they were refused as currency and coins of lower denomination – such as base shillings and groats – were increasingly shunned.

Hence, the Queen analysed the problem and formulated a solution in concert with her trusted advisers William Cecil and Thomas Gresham.

Gresham was put in charge of the programme and acted swiftly and efficiently. Within a year (1560-61) the debased money had been withdrawn, melted down and replaced with newly minted Elizabethan coins of precious metal. The Crown even made a healthy profit from the exercise, estimated at £50,000.

The restoration of the nation’s coinage improved the dealings of English merchants abroad and secured trust and respect from the City for Queen Elizabeth I and her government. The success of the initiative and the maintenance of the integrity of England’s coinage throughout Queen Elizabeth’s reign, led to economic recovery. The confidence that it bred also allowed for the expansion in trade and industry that followed.

Most currencies of had the ruling monarch's face imprinted on them

Literature

As the economy improved, more people learned how to read and write. It was marked by a strong national spirit, by patriotism, by religious tolerance, by social content, by intellectual progress & by unbounded enthusiasm. The Elizabethan Era had a large growth of literature because Queen Elizabeth supported and encouraged the fine arts by allowing a greater degree of freedom over what could be written. The literature of the time was characterized by a new energy, originality, and confidence based on Renaissance humanism.

Another factor that contributed to the literature during the Elizabethan Era was the Renaissance. The Renaissance coincided with Queen Elizabeth I's reign, during which there was an incredible growth in the areas of English poetry, music and literature. It was a period of restoration filled with peace and prosperity which allowed people to look beyond their normal writings and start exploring and experimenting with new ideas. This period’s literature is characterized by a rebirth of English classical learning and a rediscovery of ancient Greek and Roman authors.

The Elizabethan Era was known as the Golden Age in England’s history when literature flourished under the rule of Queen Elizabeth I. Secondly, the tumultuous events that happened prior to and during the Elizabethan era provided much inspiration to writers at the time. The Protestant Revolution and the defeat of the Spanish Armada influenced what the authors during this time period were writing about.

The Elizabethan Era gave birth to three of the most renowned and remembered authors William Shakespeare, Edmund Spenser, and Christopher Marlowe. All of these authors were influenced by the Elizabethan Era and then went on to influence other time periods and eras with their literary works, such as poems, dramas, and plays.

William Shakespeare

Edmund Spenser

Christopher Marlowe

Military

While Henry VIII had launched the Royal Navy, his successors King Edward VI and Queen Mary I had ignored it and it was little more than a system of coastal defense. Elizabeth made naval strength a high priority. `She risked war with Spain by supporting the "Sea Dogs," such as John Hawkins and Francis Drake, who preyed on the Spanish merchant ships carrying gold and silver from the New World. A fleet review on Elizabeth I's accession in 1559 showed the navy to consist of 39 ships, and there were plans to build another 30. Elizabeth kept the navy at a constant expenditure for the next 20 years, and maintained a steady construction rate.

The English boats were generally smaller, faster, more heavily gunned and more manoeuvrable than the large Spanish Galleons. That was a deciding factor in England’s victory of the Spanish Armada, as the smaller ships were faster and were able to relentlessly hassle the Spanish boats.

Spanish ships (above) were shorter and had a higher deck in comparision to its English counterpart (below).

Elizabeth’s upgrade of the English Navy during her reign set the foundation for the modern British Navy we have today.

International Relations

When Elizabeth ascended to the throne, England’s finances were not exactly robust. Wanting to conserve her energy while building up the national treasury, Elizabeth did her best to avoid wars with other foreign powers. Her chief motive in the foreign sphere was that England should remain a free and independent nation.

Her foreign policy was mainly a defensive one as she managed to maintain amiable relationships with some of the most powerful contemporary empires and supported Protestant struggles across Europe.

Trade and Explorations

The Treaty of Tordesillas

In 1494, when Spain and Portugal divided the New World between them, with the Pope’s approval. A line was drawn down the Atlantic, between the Americas and Africa, so that North and South America fell to Spain, while Brazil went to the Portuguese.

Spain benefited greatly from the treaty. Columbus had already, in 1492, discovered Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic) and other Caribbean islands. Spanish power was established in Central America, including Panama, and the north and western coasts of South America, after the conquest of the Aztec and Inca empires. ‘The north coast of South America and the islands had an abundance of pearls, gold and gemstones, but the biggest stroke of luck was the vast silver mine at Potosi, Peru. By 1545 the production and mining of these precious goods were being shipped to Spain in such huge quantities that European commerce was forever changed.

The Portuguese had already established trading posts down the west coast of Africa. By 1600 they had contacts on the east African coast, Macao, India, Ceylon and ‘the Spice Islands’, Sumatra and Java, with other islands in the East Indian archipelago, as well as the southern end of the Burmese peninsula and Japan. They monopolised the profitable spice trade.

From 1598, the Dutch, and occasionally the English, attacked the Spanish/Portuguese far eastern empire as part of their campaign against Spain, with a view to capturing the spice trade. (Spain had annexed Portugal in 1580, but left the administration of Portugal’s far eastern empire in Portuguese hands.)

The English explorers

One of the first explorers to take part in the era of Elizabethan exploration was Martin Frobisher, who led three expeditions (1576–78) in search of the north-west passage which he was convinced existed round the north of the American continent and then west and south to the riches of Asia. He failed to find the route, and the ‘gold-bearing ore’ he brought back produced only heated arguments.

An alternative route might lie round the north of Russia. Richard Chancellor had sailed to Archangel in 1553 and travelled overland to Moscow, where Ivan IV, called ‘the Terrible’, gave him favourable trading terms. The Muscovy Company, incorporated in 1555 as the first English joint-stock company, pushed south to Astrakhan, and on to Persia, trading English cloth for oriental silks and spices arriving via the Silk Road. Another joint stock company, the Turkey Company, opened trading relations with Baghdad, and prospected an overland route to Bengal, Burma and Siam. But the overland route to the East was too vulnerable to be practicable. The only way to India and the Spice Islands had to be by sea.

Search for new trade

The search for new markets during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I helped to boost England’s maritime confidence.

The Dutch were England's major client for cloth exports, and the port of Antwerp, in the Netherlands, was the commercial centre.

During this time, the Netherlands was also a Spanish province, which meant the stability of the European market for English cloth, and the availability of imports in return, were affected by the state of relations between Spain, England and the Netherlands. In a time where Anglo-Spanish relations were at an all-time low, it would be best to find backups as business tidings were very likely to change based on the political landscape.

Trade with the Dutch

Anglo-Russian trading

Financial problems meant that Antwerp had been in decline since 1551, so other alternatives started to be sought. A search for a navigable North-East Passage to China, through the Arctic seas above Russia, was commissioned by private investors with royal support in 1553. Although the primary aim of the mission failed, the expedition did succeed in establishing a direct trade with Russia.

The need to spread the financial risk of long-distance ventures among small investors led to the creation of the first joint-stock company. The Muscovy Company, founded during Queen Mary’s reign in 1555, had 201 shareholders, including Elizabeth. Joint-stock companies continued to thrive during Queen Elizabeth I reign.

The port of Archangel in the White Sea was founded during Queen Elizabeth's reign and the Muscovy Company flourished. Anthony Jenkinson, one of the Company's most successful merchants, soon became the Queen's ambassador to the court of Tsar Ivan IV. The Muscovy Company continued to search for viable sea routes to the East but, when they proved too hazardous, began to explore overland routes with the Tsar's blessing.

The White Sea

The port of Archangel

The search continues

In 1564, attention was drawn to solving the unhealthy reliance on the port of Antwerp and the impact of fluctuating Anglo-Spanish relations.

The outbreak of the Dutch revolt against Spanish rule in 1566, and deteriorating Anglo-Spanish relations, made the situation even more critical. A secure European market was essential, as was the need for new ones. New markets were opened in Germany and the search for others gathered momentum, both as outlets for English cloth and as direct sources of imported goods.

During the 1570s and 1580s the search for a North-East and North-West Passage to open up new markets in the East continued. Licensed by Elizabeth, backed by the Muscovy Company and tutored in navigation by John Dee, explorer and privateer Martin Frobisher led the search for a North-West Passage above present-day Canada.

Frobisher and his men made three voyages between 1576 and 1578, sailing across the Atlantic Ocean and landing on Baffin Island in northern Canada. The land was claimed for Elizabeth, who named it 'Meta Incognita' (unknown boundary).

Route of Martin Frobisher

Elizabeth had no money to fund a world-wide colonising campaign, and she could not afford to be seen openly encouraging attacks on Spanish and Portuguese possessions, but she was quite prepared to subsidise foreign trading ventures by her subjects, as long as she shared in the profit. Intentional provocation of other naval powers far superior to hers would ultimately result in war, something she could not afford at the moment. Trade on the other hand was much more profitable, and was only affected by the weather which would sink the ships.

Slave Trade

In 1562, John Hawkins identified a new and profitable commodity: African slaves. The Spanish New World colonies needed labourers to replace the indigenous Amerindians, who were being killed off by European diseases. Hawkins developed the ‘triangular trade’. He bought or captured men and women from Africa, whom he sold to the Spanish colonists in America, in exchange for Spanish gold and gemstones, which he sold in England. The Spanish resented this intrusion into their markets, and Hawkins had to give it up after a few years, but the precedent had been set for a sinister trade that brought fortunes to British slavers until its final abolition in the British Empire, in 1807.

Slaves were commonly captured before being taken back to England to be sold

Shift of Trade Center

Wool had been England’s main export for centuries. In about 1585 the European market for most major commodities shifted from Antwerp to Amsterdam, which became the mercantile centre of the world. Here an English merchant could trade wool and woollen cloth, for Russian furs and Chinese silk, lapis lazuli from Afghanistan and alum from Italy, far eastern spices and wines from Portugal, the Rhineland and France. There was of course no common currency. International finance was in the capable hands of Genoese bankers.

Trade in the Baltic Region

The Hanseatic merchants had had a special relationship with England since the 12th century. They were a German medieval commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds and market towns in Central and Northern Europe. The guild had a monopoly of English trade with the Baltic, importing the hemp for ropes and sail cloth and timber for ships, both vital to English defences, and grain which they sold at high prices when English harvests failed. This method of price gouging would have earned them some resentment from the English. Their favourable tax status made them even more unpopular. At last, in 1598, their privileged position ended and they were banished, opening Baltic trade to English merchants.

Colonies

In 1583 Humphrey Gilbert discovered the island of Newfoundland, and claimed it for England. It was a bleak land with an inclement climate, but the cod which then abounded off its shores promised a steady income, admittedly lacklustre when compared to gold and jewels but at least a colony they had a valid claim to. Newfoundland was England’s first colony in the New World.

Establishment of Newfoundland