Chapter IV: Notable Disputes

Edward Seymour

Thomas Seymour

Thomas Seymour asked the 13-year-old Princess Elizabeth to marry him by letter in February 1547, within a month of her father, Henry VIII’s death. Seymour probably believed that marrying Elizabeth would increase his hold on power; his brother, Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, had just been made Lord Protector. Thomas was probably envious of his brother’s position. Elizabeth rejected his proposal by letter, saying she was too young (she was 13 years old; he was 38, 25 years older than she) and would be in mourning for her father for two years.

Within a month or so of receiving her rejection, Thomas Seymour married the queen dowager Katherine Parr, Henry VIII’s widow and Elizabeth’s stepmother. Katherine had been in love with him since before her marriage to Henry, but it is possible that Thomas married her to get closer to Elizabeth. At almost exactly this time, Elizabeth started living with Katherine. Soon afterwards, Thomas moved in to live with his new wife.

Now with Elizabeth, living in his household, Thomas had a golden opportunity to groom Elizabeth into considering the possibility of marriage with him. This would secure his position as the king of England when Elizabeth would eventually become queen.

Elizabeth endured Thomas Seymour bursting into her rooms in the morning, tearing back the curtains of her bed, and tickling her until she could get away. Despite this, she never once neglected her studies. This was a remarkable achievement, as Seymour’s acts became less cheeky and more sexual as time went on, surprising her in the halls, and heckling her servants for access to her apartment at all hours.

According to testimonies given in 1549 by Elizabeth’s governess and companion, Kat Ashley, and her accountant, Thomas Parry, from June 1547 – within days of Seymour’s arrival – Elizabeth started to receive early-morning visits from him. He would “make as though he would come at her” and she would shrink back. The next day, she rose earlier so that he wouldn’t find her in bed, but when he arrived, she was still dressed only in a nightdress, he in a short nightgown, “barelegged in his slippers”. He greeted her and reached out to “strike her on the back or the buttocks familiarly”. Another time he climbed into Elizabeth’s bed, while she was still in it. She continued to get up earlier – if she were dressed, he would bid her good morning and then go on his way.

Kat Ashley testified that she grew concerned about his visits, and came to sit in her mistress’s rooms in the early mornings, but that Seymour continued his behaviour. She maintained that she told him to “go away for shame” and squared up to him on one occasion saying that word of his behaviour was getting out. Seymour replied that “he meant no evil”.

Soon after this incident, Katherine asked Kat Ashley to keep watch on Elizabeth’s behaviour. She claimed that Seymour claimed to have seen Elizabeth “cast her arms about a man’s neck” in an embrace, but no one else in the household had seen it and Ashley came to believe that Katherine had made it up to get her to spy on Elizabeth and Seymour.

Katherine and Seymour moved to his London house for several months, and Elizabeth did not go with them. When in spring 1548, she arrived to join them, he started up his morning visits again. Kat Ashley says she again reprimanded him for coming in a state of undress into “a maiden’s chamber”.

In June 1548, Katherine wrote to Seymour, and asked Elizabeth to arrange a messenger to get the letter to him. Elizabeth wrote on the outside of the letter, in Latin, “Thou, touch me not”, then deleted it, and wrote instead, “Let him not touch me” – suggesting his advances were unwanted, but that she feared speaking too directly to him about it.

Katherine, although madly in love with Thomas, was becoming suspicious. In an effort to prove to his wife that these romps were all in good fun, he enlisted Katherine as his “accomplice”, having her assist in some of his predatory acts. While there is no contemporary record of Elizabeth ever being molested by Thomas Seymour, his attentions were no doubt sinister. It is the method of operation of a predator to take advantage of those whom he is close to, and to involve his partner in his own dubious activities. Thomas Seymour did both. It may also seem that Catherine was overjoyed her husband shared the close relationship she did with her stepdaughter. But over time, as Elizabeth matured and Thomas began going overboard in his antics, she began to realise it was something more concerning. This would worsen when she fell pregnant…

Scarcely two months into Ascham’s employment in 1548, the Queen Dowager became pregnant with Thomas Seymour’s child. She was in her late 30’s, even now a precarious age to have a first child, much less the 16th century. The queen was overjoyed, and a little frightened over her new condition. Katherine's happiness was interrupted when apparently Thomas Seymour got far too friendly with Elizabeth; He was overseen grabbing and holding her in his arms in the garden. This enraged Katherine and Elizabeth was sent away to live with Katherine Parr’s good friends Sir Anthony and Lady Denny, indefinitely, where Roger likely changed his venue of teaching to.

Katherine may have sent her stepdaughter away, but she did not take the separation lightly, and her actions and surviving accounts of the matter suggest that she sent Elizabeth away for her own safety. If Thomas were to damage Elizabeth’s chastity, her life would be ruined, and great punishment would be exacted upon all her caregivers. Besides, the heavily pregnant Katherine knew that she would soon have been going into confinement and would not be able to stop Seymour’s advances.

Though rather traumatised by this disturbing period, Elizabeth and Katherine exchanged affectionate letters with each other. Elizabeth continued to thank her stepmother for her kindness and diligence in keeping an eye and ear out for all who sought to sully her reputation, something that Elizabeth would never again take so lightly because of this episode. She signed the letter, ‘Your Highness’ humble daughter, Elizabeth.’

When Katherine died from childbirth complications on 5 September 1548, Elizabeth was understandably devastated at the loss of an integral maternal figure. More so, she was now without a protector, and the next chapter in her life would be far more dangerous than the first. Seymour would continue his unwanted advances toward her. The newly single Seymour sent his nephew, John Seymour, to accompany Elizabeth as she moved to set up her own household at Hatfield soon after, and (according to Thomas Parry), Seymour told John to enquire of Elizabeth: “whether her great buttocks were grown any less or no?”

In January 1549, Seymour was arrested for trying to kidnap the king, marry Elizabeth without the council’s consent, and make himself de facto king. Elizabeth, Kat Ashley, and Thomas Parry, would be imprisoned and questioned about the Admiral’s intentions to determine whether they had been privy to his plots. Elizabeth, of course, had not, though Kat had verbalised to Thomas Parry that the match could have been the end to all her charge’s problems. Although that notion was more than likely shot down by Elizabeth.

Elizabeth endured being interrogated day after day, by Robert Tyrwhit, in an attempt to implicate her in the Admiral’s plot for the throne. Tyrwhit frequently reported his frustration with the princess. Thankfully, Elizabeth was eventually able to ultimately ensure her own, Parry’s and Kat Ashley’s freedom. Thomas Seymour was deservedly not as fortunate, and he would be beheaded for a multitude of crimes: attempted kidnapping of his nephew, counterfeit money, and most severely, treason. Elizabeth would allegedly remark on his execution day 20 March 1549, ‘This day died a man with much wit, and very little judgement.’

Erik XIV of Sweden

Erik XIV

Around the 1550s, against his father’s wishes, Erik XIV of Sweden entered into marriage negotiations with the future Queen Elizabeth I of England and pursued her for several years. He sent her love letters in Latin and dispatched his uncouth half-brother John to her court to press his suit, but Elizabeth managed to keep Erik dangling for years without any real intention of marrying him, but even refusals could not deter Erik from his wooing.

Thankfully, this state of romantic limbo did not damage Anglo-Swedish relations, but may have contributed to instability in Erik’s own rule. The rejection may have helped fuel his paranoiac behaviour towards his courtiers, which likely worsened after his wife, Karin’s death. All this culminated in him being replaced in favour of his half brother, and then being poisoned to prevent his supporters from attempting to restore his position.

Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex

Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex

Queen Elizabeth I's relationship with Robert Devereux, the 2nd Earl of Essex, greatly influenced the latter part of her reign, and resulted in Essex's execution in 1601. After the Armada, many of Elizabeth's closest friends and advisers passed, including Dudley (1588), Walsingham (1590), Hatton (1591) and Cecil (1598), leaving the ageing Queen increasingly isolated. A number of them were replaced by younger relatives, notably Dudley's stepson Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, and Robert Cecil, William Cecil's son.

Although Robert Dudley and William Cecil were often at odds over administrative policy, it was nothing compared to the rivalry that developed between their sons.

Devereux first came to court in 1584, and by 1587 had become a favourite of the queen, who relished his lively mind and eloquence, as well as his skills as a showman and in courtly love. In June 1587 he replaced his stepfather, the Earl of Leicester as Master of the Horse. After Leicester's death in 1588, the queen transferred the late Earl's royal monopoly on sweet wines to Essex, providing him with revenue from taxes. In 1593, he was made a member of her Privy Council.

It is reported that his friend and confidant Francis Bacon warned him to avoid offending the queen by attempting to gain power and underestimating her ability to rule and wield power. However, despite this advice, Essex did not seem to take it to heart. He underestimated the queen and his later behaviour towards her lacked due respect and showed disdain for the influence of her principal secretary, Robert Cecil. On one occasion during a heated Privy Council debate on the problems in Ireland, the queen reportedly cuffed an insolent Essex round the ear, prompting him to half draw his sword on her.

Route of the English Armada

In 1589, he took part in the English Armada, despite the queen having ordered him not to take part. The English Armada was defeated with 40 ships sunk and 15,000 men lost. In 1591, he was given command of a force sent to the assistance of King Henry IV of France. In 1596, he distinguished himself by the capture of Cádiz. During an expedition to the Azores in 1597, he defied the queen's orders, pursuing the Spanish treasure fleet without first defeating the Spanish battle fleet.

When the 3rd Spanish Armada first appeared off the English coast in October 1597, the English fleet was far out to sea, with the coast almost undefended, and panic ensued. Fortunately, a storm dispersed the Spanish fleet, ultimately resulting in Spanish withdrawal. This further damaged the relationship between the queen and Essex.

Essex's greatest failure was as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, a post which he talked himself into in 1599. An Irish rebellion was in its middle stages, and no English commander had been successful in putting it down.

Essex led the largest expeditionary force ever sent to Ireland—16,000 troops—with orders to put an end to the rebellion. He departed London to the cheers of the queen's subjects, and it was expected the rebellion would be crushed instantly. Essex had declared that he would confront the rebel leader, O'Neill in Ulster, a region in Northern Ireland. Instead, he led his army into southern Ireland, where he fought a series of inconclusive engagements, wasted his funds, and dispersed his army into garrisons, while the Irish won other battles in other parts of the country. Rather than face O'Neill in battle, Essex entered a truce that some considered humiliating to the Crown and to the detriment of English authority. The queen told Essex that if she had wished to abandon Ireland it would scarcely have been necessary to send him there.

Essex was to proceed to Ulster in Northern Ireland (above),

where instead he went to regions in the Republic of Ireland, in the South (above).

In all of his campaigns, Essex secured the loyalty of his officers by conferring knighthoods, an honour the queen dispensed sparingly, and by the end of his time in Ireland more than half the knights in England owed their rank to him. With a large number of knights on his side, he was able to gain enough power to challenge Cecil.

Relying on his general warrant to return to England, given under the great seal, Essex sailed from Ireland on 24 September 1599 and reached London four days later. The queen had expressly forbidden his return and was surprised when he presented himself in her bedchamber, before she was properly wigged or gowned. On that day, the Privy Council met three times, and it seemed his disobedience might go unpunished, but the queen did confine him to his rooms with the comment that "an unruly beast must be stopped of his provender." Even Elizabeth was slowly getting tired of her favourites’ disregard for decorum.

Essex appeared before the Privy Council on 29 September, when he was compelled to go through a five-hour interrogation. The Council—his uncle, 1st Earl of Banbury included—took a quarter of an hour to compile a report, which declared that his truce with O'Neill unnecessary and his proceeding to Southern Ireland instead of Northern Ireland under desertion of duty. He was committed to house arrest on 1 October, and he blamed Cecil and Raleigh for the queen's hostility. Raleigh advised Cecil to see to it that Essex did not recover power, and Essex appeared to heed advice to retire from public life.

However, in November, the queen seemed to change her mind about the treaty and considered forgiving Essex and allowing his return to court. Others in the council were willing to justify Essex's return from Ireland but Cecil kept up the pressure to not pardon him easily. On 5 June 1600, Essex was tried before a commission of 18 men. He had to hear the charges and evidence on his knees. Essex was convicted, deprived of public office, and returned to virtual confinement.

In August, his freedom was granted, but the source of his income—the sweet wines monopoly—was not renewed. His situation had become desperate, and he decided to rebel against the crown. In early 1601, he began to fortify his town mansion, and gathered his followers.

On the morning of 8 February, he marched with a party of nobles and gentlemen and attempted to force an audience with the queen. Cecil immediately had him proclaimed a traitor.

William Knollys denied hearing Cecil making that statement, ensuring the latter's innocence.

On 19 February 1601, Essex was tried before his peers on charges of treason. Essex was also charged with holding the Lord Keeper and the other Privy Councillors in custody "for four hours and more." Part of the evidence showed that he was in favour of toleration of religious dissent. In an attempt to defend himself, he sought to incriminate Cecil of treason, claiming Cecil stated, “none but Spain had right to the English Crown. The witness whom Essex expected to confirm this allegation, his uncle William Knollys, was called and denied hearing Cecil make the statement. Cecil was innocent and Essex was still a traitor.

Essex was found guilty and, on 25 February 1601, was beheaded on Tower Green. It was reported to have taken three strokes by the executioner Thomas Derrick to complete the beheading. Ironically, the one to execute Essex had been pardoned by him previously on the condition that the former became an executioner.

Philip II of Spain

Philip II

Now aged 37, Mary turned her attention to finding a husband and producing an heir, which would prevent the Protestant Elizabeth (currently first in line to the Tudor throne) from succeeding to the throne. Her first cousin Charles V suggested she marry his only legitimate son, Philip. The Spanish prince had been widowed a few years before by the death of his first wife, Maria Manuela of Portugal, mother of his son Carlos and was the heir apparent to vast territories in Continental Europe and the New World. Both Philip and Mary were descendants of John of Gaunt and in Mary's case, the ancestry was by double lineage. As part of the marriage negotiations, a portrait of Philip by Titian was sent to Mary in the latter half of 1553.

Elizabeth I's residence when she was under house arrest

after her proven innocence in the wake of the Wyatt rebellion.

Parliament unsuccessfully petitioned Mary to consider marrying an Englishman, fearing that England would be relegated to a dependency of the Habsburgs. The marriage was unpopular with the English; Mary’s ministers opposed it on the basis of patriotism, while Protestants were motivated by a fear of Catholicism. When Mary insisted on marrying Philip, insurrections broke out and the Wyatt rebellion broke out. Mary declared publicly that she would summon Parliament to discuss the marriage and if Parliament decided that the marriage was not to the kingdom's advantage, she would refrain from pursuing it. The rebellion was quickly quashed and all perpetrators were executed soon after. Elizabeth, though protesting her innocence in the Wyatt affair, was imprisoned in the Tower of London for two months, then put under house arrest at Woodstock Palace.

Mary I's maternal grandparents, Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile, both maintaining sovereignty of their respective realms after marriage.

Don Carlos, heir apparent to the Spanish throne after Philip II

Mary was England's first queen regnant. Further, under the English common law doctrine of jure uxoris, the property and titles belonging to a woman became her husband's upon marriage, and it was feared that any man she married would thereby become King of England in fact and name. Mary's grandparents Ferdinand and Isabella had retained sovereignty of their respective realms of Aragon and Castile during their marriage; but there was no precedent to follow in England. Under the terms of Queen Mary's Marriage Act, Philip was to be styled "King of England", all official documents were to be dated with both their names, and Parliament was to be called under the joint authority of the couple, for Mary's lifetime only. England would not be obliged to provide military support to Spain in any war, and Philip could not act without his wife's consent or appoint foreigners to office in England. Philip was unhappy with these conditions but ready to agree for the sake of securing the marriage.

Unfortunately for Mary who was deeply in love with her young Spanish husband, he did not return her feelings. On his side, the marriage was a purely strategic one. A future child of Mary and Philip would be not only heir to the throne of England but also heir to the Spanish Empire in the event that Philip's eldest son, Don Carlos, died.

The two were married at Winchester Cathedral

Philip II(left) and Mary I (right)

To elevate his son to Mary's rank, Emperor Charles V ceded to Philip the crown of Naples as well as his claim to the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Mary thus became Queen of Naples and titular Queen of Jerusalem upon marriage. Their wedding at Winchester Cathedral on 25 July 1554 took place just two days after their first meeting. Philip could not speak English, and so they spoke a mixture of Spanish, French, and Latin.

The marriage was a disastrous and very unaffectionate one for Mary and after her false pregnancy, Philip left for Flanders to wage war against France, which undoubtedly left Mary in a depression. She considered these disgraces "God's punishment" for her having "tolerated heretics" in her realm.

Pope Julius III

Mary was a staunch Catholic, and in her view, Protestants did not worship the true God and were heretics. Mary rejected the break with Rome her father instituted and the establishment of Protestantism by her brother's regents. Philip persuaded Parliament to repeal Henry's religious laws, returning the English church to Roman jurisdiction. Reaching an agreement took many months and Mary and Pope Julius III had to make a major concession: the confiscated monastery lands were not returned to the church but remained in the hands of their influential new owners. By the end of 1554, the pope had approved the deal, and the Heresy Acts were revived.

The heretic acts were a law that granted Mary the authority to deal with heretics as she pleased. That was a bad move as the first five burnings occurred over five days in February 1555. The number and frequency of those burnings only ramped up after her depression, which no doubt brought instability and struck fear into the people's hearts.

Soon after Mary’s death in 1558, likely in an attempt to prolong his tenure on the English throne, Philip I sought to marry Elizabeth.

Unfortunately for him, Elizabeth had the backing of Parliament behind her rejection of Philip. She was a Protestant, and her regime was to reflect those views. Philip II was a Catholic and her sister’s widower. In addition, the country had proven even more wary of Catholic monarchs after Mary’s prosecution.

Even now, Elizabeth’s rule was still an unstable one. There were still foreign Catholics aboard who supported her cousin, Mary of Scots instead. Philip was involved in multiple plots to replace Elizabeth with her more popular, Catholic cousin.

Anglo-Spanish relations would only worsen from there.

In the wake of the Ridolfi plot

The first was the Ridolfi Plot which emerged in the aftermath of the failed Northern Rebellion. Roberto Ridofi, an Italian banker, had been involved in the Northern Rebellion. Having seen it fail, he became convinced that the only way to overthrow Elizabeth was through a combination of uprising and overseas intervention. With this in mind, he approached a number of leading Catholic nobles as well as making advances to foreign powers. The plot was to have an invasion of England by the Duke of Alba from the Netherlands alongside a simultaneous uprising of English Catholics. Ridolfi intended that Elizabeth would be killed and replaced by Mary, Queen of Scots. Mary would marry the Duke of Norfolk. Ridolfi gained the support of both Mary, Queen of Scots and the Duke of Norfolk for the plot. The plot gained the support of the Pope and King Philip II of Spain.

The sea dogs and spies, Sir Walter Raleigh (left), Sir John Hawkins (middle ) and Sir Francis Drake (right)

The sea dogs would go on to launch a series of imperial funded pirating against Spanish ships

In 1571 John Hawkins, one of Walsingham’s spies, learnt of the plot from the Spanish. The spymaster’s men then ensnared Norfolk. Letters and gold were intercepted. Norfolk’s staff were questioned, interrogated and tortured to reveal details of the plot. The letters, written largely in code, were deciphered when the code key was found in Norfolk’s home.

The letters implicated Norfolk and Mary, Queen of Scots. Norfolk admitted, in part at least, his involvement in the plot. Norfolk was put on trial, found guilty and beheaded in January, 1572. Ridolfi left England before the plot’s discovery, and the Spanish ambassador was banished due to Spanish complicity in the plot.

The second was the Throckmorton Plot which planned to utilise French and Spanish troops to oust Elizabeth and replace her with Mary. The plot was devised by brothers Francis and Thomas Throckmorton along with his brother, agents from Spain. English spies uncovered the plot and arrested Throckmorton. He was sentenced to death and the Spanish Ambassador, who was implicated, was sent back to Spain.

Sir Francis Drake was respondsible for pirate attacks on Spanish ships and the delay of the Spanish Armada.

The hatred between Spain and England was not a unilateral one as there were multiple instances of imperial funded pirating on Spanish ships. In 1568, the Duke of Alva had 5 of his ships intercepted and robbed of £85,000 in gold bullion. The gold would have paid all his soldiers for a few years. Ten years later, on his circumnavigation of the globe, Sir Francis Drake attacked Spanish ships near Lima. Again a huge amount of gold was plundered. The English treasury was in need of gold, particularly at the beginning of Elizabeth’s reign. England also had a historic control of the Channel, the former of these incidents may have been asserting this supremacy.

Things came to a head when Elizabeth decided to execute her cousin, Mary of Scots. The execution of a Catholic ally was enough for Philip to launch an invasion against England to restore Catholicism to England. In addition, English funded piracy on Spanish ships had proved a major motivation for the Spanish invasion but the execution of Mary was the final straw.

Francis Walsingham was instrumental in discovering plans for the Spanish invasion as well as laying much of the groundwork that led to England's victory.

Thankfully, it was due to the spy network of Secretary of State, Francis Walsingham who discovered the invasion and made the necessary preparations for war with Spain.

In May 1588, after several years of preparation, the Spanish Armada set sail from Lisbon under the command of the Duke of Medina-Sidonia. When the 130-ship fleet was sighted off the English coast later that July, Howard and Drake raced to confront it with a force of 100 English vessels.

The English fleet and the Spanish Armada met for the first time on July 31, 1588, off the coast of Plymouth. Relying on the skill of their gunners, Howard and Drake kept their distance and tried to bombard the Spanish flotilla with their heavy naval cannons. While they succeeded in damaging some of the Spanish ships, they were unable to penetrate the Armada’s half-moon defensive formation.

Over the next several days, the English continued to harass the Spanish Armada as it charged toward the English Channel. The two sides squared off in a pair of naval duels near the coasts of Portland Bill and the Isle of Wight, but both battles ended in stalemates.

By August 6, the Armada had successfully dropped anchor at Calais Roads on the coast of France, where Medina-Sidonia hoped to rendezvous with the Duke of Parma’s invasion army.

Desperate to prevent the Spanish from uniting their forces, Howard and Drake devised a last-ditch plan to scatter the Armada. At midnight on August 8, the English set eight empty vessels ablaze and allowed the wind and tide to carry them toward the Spanish fleet hunkered at Calais Roads.

The sudden arrival of the fireships caused a wave of panic to descend over the Armada. Several vessels cut their anchors to avoid catching fire, and the entire fleet was forced to flee to the open sea.

With the Armada out of formation, the English initiated a naval offensive at dawn on August 8. In what became known as the Battle of Gravelines, the Royal Navy inched perilously close to the Spanish fleet and unleashed repeated salvos of cannon fire.

Several of the Armada’s ships were damaged and at least four were destroyed during the nine-hour engagement, but despite having the upper hand, Howard and Drake were forced to prematurely call off the attack due to dwindling supplies of shot and powder.

With the Spanish Armada threatening invasion at any moment, English troops gathered near the coast at Tilbury in Essex to ward off a land attack. Queen Elizabeth herself was in attendance and gave a speech to her troops.

Shortly after the Battle of Gravelines, a strong wind carried the Armada into the North Sea, preventing the naval forces from joining with the infantry on land. Due to lack of disease and rampant disease, Spain sought to give up the invasion and return home.

The Spanish Armada had suffered heavy losses during its battle of the English, but the journey home would claim far more lives. The Spanish navy faced many storms on its journey home, sinking and destroying much of what remained.

By the time the Spanish Navy arrived home, almost half of the fleet and personnel had been decimated. This fight may have ended in England's favour, but it was hardly the end of the conflict between Philip II and Elizabeth I .

In 1589, Queen Elizabeth launched a failed “English Armada” against Spain. On the other hand, the Spanish attempted two further Armadas, in October 1596 and October 1597. The 1596 Armada was destroyed in a storm off northern Spain; it had lost as many as 72 of its 126 ships and suffered 3,000 deaths. The 1597 Armada was frustrated by adverse weather as it approached the English coast undetected.

The conflict between the Habsburg dynasty and the English Crown would drag on beyond Philip II and Elizabeth I’s deaths in 1598 and 1603 respectively. It wasn’t until 1604 that a peace treaty was finally signed ending the Anglo-Spanish War as a stalemate.

Ivan the Terrible

Ivan IV, posthumously known as Ivan the Terrible

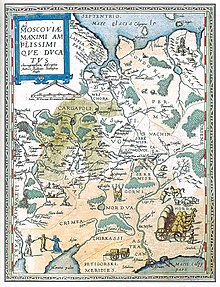

Tsardom of Muscovy

In 1551, on the initiative of the famous astronomer John Dee, the ‘Company of Merchant Adventurers for the Discovery of Regions, Dominions, Islands and Places unknown’ was founded. The company’s goal was to find a route to China. They didn’t succeed in finding it. Instead, the English merchants had established regular trade connections with the Tsardom of Muscovy. The Englishmen founded the Muscovy Trading Company and began bringing in tin, cloth and weapons. In return, they received hemp, timber, blubber and tar. Ivan the Terrible granted the company the right to conduct free trade in his territory.

English Envoy, Anthony Jenkinson

The trade growth between the countries led to a lively business correspondence between Ivan the Terrible and Elizabeth I. At that, not every topic could be trusted to paper for fear of others modifying the letters to send false information. Information was instead passed through English envoy Anthony Jenkinson. In the end, from business negotiations the Russian monarch proceeded to seek the hand of the queen.

Ivan IV, now known as Ivan the Terrible for his acts of violent tyranny from the 1560s to his death, was unhappily married to his second wife and sought a better partner. In addition, a marriage to an English monarch allowed him to seek asylum in England, in case his rule took a turn for the worse.

Elizabeth I, upon receiving his proposal, carefully considered her options. While a marriage to Ivan IV would prove miserable, Russia was one of the country’s biggest trade partners and she had to proceed carefully.

Elizabeth stalled for time, waiting until Ivan gave up. Unfortunately, these tactics did not work on Ivan, sensing a refusal in the absence of an immediate reply. He was enraged.

His reply was a harsh one, where he stated, “ Thyself thou art nothing, but a vulgar wench and thou behavest like one! I give up all intercourse with thee. Moscow can do without the English peasants.” At the end of his reply, he remarked contemptuously that Elizabeth lived not like a real queen, but like a “common girl”, hinting at her inability to be a ruler in her own country, instead redirecting the power to other people. Their correspondence stopped for a long 12 years.

In that period, as an act of retaliation, Ivan opened his port to other foreign nations, and it was with great difficulty that England was able to assume trade. Thankfully, the incident proved but a mere hiccup as Anglo-Russian relations remained amiable late into the Elizabethan era. Although considering Ivan’s track record of his other six wives after the death of his first, where he reportedly poisoned one, drowned another for adultery, had another poisoned by a political enemy, three sent to convents, with two dying under suspicious circumstances, and one surviving him, it is likely Elizabeth made the right decision to not proceed in the end.

Mary of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567. She was the only surviving legitimate child of James V of Scotland, solidifying her claim to the throne.

Catholic Cardinal David Beaton

James Hamilton, Earl of Arran

As Mary was a six-day-old infant when she inherited the throne, Scotland was ruled by regents until she became an adult. From the outset, there were two claims to the regency: one from the Catholic Cardinal Beaton, and the other from the Protestant Earl of Arran, who was next in line to the throne. Beaton's claim was based on a version of the king's will that his opponents dismissed as a forgery. Arran, with the support of his friends and relations, became the regent until 1554 when Mary's mother managed to remove and succeed him.

Dauphin Francis

Mary of Scots and Dauphin Francis

King Henry VIII of England took the opportunity of the regency to propose marriage between Mary and his own son and heir, Edward, but the treaty fell through. Henry VIII would resort to military campaigns in Scotland to force them to accept the treaty, prompting Mary to be sent away for her safety. Soon after, her regents turned to France for assistance. King Henry II of France proposed to unite France and Scotland by marrying the young queen to his three-year-old son, the Dauphin Francis. On the promise of French military help and a French dukedom for himself, Arran agreed to the marriage.

<>With her marriage agreement in place, five-year-old Mary was sent to France to spend the next thirteen years at the French court. On 4 April 1558, Mary signed a secret agreement bequeathing Scotland and her claim to England to the French crown if she died without issue. Twenty days later, she married the Dauphin at Notre Dame de Paris, and he became king consort of Scotland.

In 1561, the Dauphin, still in his teens, died. Her mother had died the year before. Hence Mary was recognised as the ruler of Scotland. However, she refused to further solidify the treaty, causing her to be sent back to Scotland where she assumed rule.

As a devout Catholic, she was regarded with suspicion by many of her subjects, as Scotland was torn between Catholic and Protestant factions. To the surprise and dismay of the Catholic party, Mary tolerated the newly established Protestant ascendancy. Her privy council of 16 men, was mainly dominated by Protestants, only 4 of them were Catholic.

Mary's uncle, Cardinal de Lorraine

Mary then turned her attention to finding a new husband from the royalty of Europe. When her uncle, the Cardinal of Lorraine, began negotiations with Archduke Charles of Austria without her consent, she angrily objected and the negotiations foundered. Her own attempt to negotiate a marriage to Don Carlos, the mentally unstable heir apparent of King Philip II of Spain, was rebuffed. Elizabeth I suggested she marry English Protestant Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester. The proposal came to nothing, most likely because the intended bridegroom was unwilling.

Mary had briefly met her English-born half-cousin Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, in February 1561 when she was in mourning for Francis. Darnley's parents, the Earl and Countess of Lennox, were Scottish aristocrats as well as English landowners. They sent him to France ostensibly to extend their condolences, while hoping for a potential match between their son and Mary. Mary fell in love with the "long lad", as Queen Elizabeth called him since he was over six feet tall. They married at Holyrood Palace on 29 July 1565.

Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley

Mary of Scots and Lord Darnley

Although her advisors had brought the couple together, Elizabeth felt threatened by the marriage because as descendants of her aunt, both Mary and Darnley were claimants to the English throne. Their children, if any, would inherit an even stronger, combined claim. The union infuriated Elizabeth, who felt the marriage should not have gone ahead without her permission, as Darnley was both her cousin and an English subject.

David Rizzio (left), Mary's closeness and alleged affair with David Rizzio (middle), Rizzio's murder (right)

Unfortunately, the happy days were not to last as before long, Darnley grew arrogant. Not content with his position as king consort, he demanded the Crown Matrimonial, which would have made him a co-sovereign of Scotland with the right to keep the Scottish throne for himself, if he outlived his wife. Mary refused his request and their marriage grew strained, although they conceived by October 1565. He was jealous of her friendship with her Catholic private secretary, David Rizzio, who was rumoured to be the father of her child. On 9 March, a group of the conspirators accompanied by Darnley dragged Rizzio from behind the pregnant Mary and stabbed him to death in front of her.

Edinburgh Castle

Mary's son by Darnley, James, was born on 19 June 1566 in Edinburgh Castle. However, the murder of Rizzio led to the breakdown of her marriage.

Soon after, Mary and a few leading nobles held a meeting to discuss the resolution of the problem that was Darnley. Divorce was considered as the first option, but it is implied they decided on murder as the end solution. Darnley feared for his safety, and after the baptism of his son at Stirling and shortly before Christmas, he went to Glasgow to stay on his father's estates. At the start of the journey, he suffered a lingering illness for a few weeks.

In late January 1567, Mary prompted her husband to return to Edinburgh. He recuperated from his illness in a house just within the city. Mary visited him daily, so that it appeared a reconciliation was in progress. On the night of 9–10 February 1567, Mary visited her husband in the early evening and then attended the wedding celebrations of a member of her household, Bastian Pagez. In the early hours of the morning, an explosion devastated Kirk o' Field. Darnley was found dead in the garden, apparently smothered. There were no visible marks of strangulation or violence on the body. A few nobles and Mary herself were among those who came under suspicion.

Lord Bothwell

By the end of February, Bothwell was generally believed to be guilty of Darnley's assassination. Darnley's father demanded that Bothwell be tried before the Estates of Parliament, to which Mary agreed, but his request for a delay to gather evidence was denied. In the absence of Lennox and with no evidence presented, Bothwell was acquitted. A week later, Bothwell managed to convince more than two dozen lords and bishops to sign the Ainslie Tavern Bond, in which they agreed to support his aim to marry the queen.

Between 21 and 23 April 1567, Mary visited her son at Stirling for the last time. On 6 May, Mary and Bothwell returned to Edinburgh. On 15 May, they were married. Bothwell and his first wife had divorced twelve days previously.

Originally, Mary believed that many nobles supported her marriage, but relations quickly soured as the marriage proved to be deeply unpopular. Catholics considered the marriage unlawful, since they did not recognise Bothwell's divorce or the validity of the Protestant service. Both Protestants and Catholics were shocked that Mary should marry the man accused of murdering her husband.

The confederate lords turned against Mary and Bothwell and raised their own army. Mary and Bothwell confronted the lords at Carberry Hill on 15 June, but there was no battle, as Mary's forces dwindled away through desertion during negotiations. The lords took Mary to Edinburgh, where crowds of spectators denounced her as an adulteress and murderer. The following night, she was imprisoned in Loch Leven Castle. On 24 July, she was forced to abdicate in favour of her one-year-old son James. Moray, her chief advisor, was made regent, while Bothwell was driven into exile.

Loch Leven Castle

On 2 May 1568, Mary escaped from Loch Leven Castle with the aid of George Douglas, brother of Sir William Douglas, the castle's owner. Managing to raise an army of 6,000 men, she met Moray's smaller forces at the Battle of Langside on 13 May. Defeated, she fled south to England. On 18 May, local officials took her into protective custody where she would be kept under house arrest for the next 19 years.

Mary apparently expected Elizabeth to help her regain her throne. Elizabeth was cautious as to Mary due to the matter’s influential political presence. Under the Third Succession Act, passed in 1543 by the Parliament of England, Elizabeth was recognised as her sister's heir, and Henry VIII's last will and testament had excluded the Stuarts from succeeding to the English throne. Yet, in the eyes of many Catholics, Elizabeth was illegitimate and Mary Stuart was the rightful queen of England, as the senior surviving legitimate descendant of Henry VII through her grandmother, Margaret Tudor, Henry VII’s sister.

Elizabeth considered Mary's designs on the English throne to be a serious threat and so confined her to a number of properties, including but not limited to Tutbury, Sheffield Castle, and Chatsworth House. These were located halfway between Scotland and London and distant from the sea.

Mary was permitted her own domestic staff. She was transported from house to house. Her chambers were finely decorated, her bed linen was changed daily and her own chefs prepared meals with a choice of 32 dishes served on silver plates. She was occasionally allowed outside under strict supervision.

Elizabeth's principal secretary William Cecil, Lord Burghley, and Sir Francis Walsingham watched Mary carefully with the aid of spies placed in her household. A number of spies were placed in her household under the pretext of servants. If Mary sent out letters, the servants would send a copy of the letter to Walsingham, who would proceed to examine it closely.

In 1571, Cecil and Walsingham (at that time England's ambassador to France) uncovered the Ridolfi Plot, a plan to replace Elizabeth with Mary with the help of Spanish troops and the Duke of Norfolk. Norfolk was executed and the English Parliament introduced a bill barring Mary from the throne, to which Elizabeth refused to give royal assent.

Mary sent letters in cipher to the French ambassador, Michel de Castelnau, scores of which were discovered and decrypted in 2022–2023. After the Throckmorton Plot of 1583, Walsingham (now the queen's principal secretary) introduced the Bond of Association and the Act for the Queen's Safety, which sanctioned the killing of anyone who plotted against Elizabeth and aimed to prevent a putative successor from profiting from her murder.

The "Bond of Association" designed by Cecil and Walsingham in 1584 stated that anyone within the line of succession to the throne on whose behalf anyone plotted against the Queen, would be excluded from the line and executed. This was agreed upon by hundreds of Englishmen, who likewise signed the Bond. Mary also agreed to sign the Bond. The following year, Parliament passed the Act of Association, which provided for the execution of anyone who would benefit from the death of the Queen if a plot against her was discovered. Because of the bond, Mary could be executed if a plot was initiated by others that could lead to her accession to England's throne.

Left: Transcripts of the Babington Plot; Middle: Mary of Scots on trial; Right: Execution of Mary of Scots

The crown had overlooked Mary’s involvement in the previous plots, likely due to lack of knowledge or her lack of participation in them. Elizabeth was also not eager to execute her as firstly, Mary was a relative, and secondly, this could set the precedent for Elizabeth’s execution in the future. However, this would change upon discovery of the Babington plot.

The long-term goal of the plot was the invasion of England by the Spanish forces of King Philip II and the Catholic League in France, leading to the restoration of the old religion. The plot was discovered by Elizabeth's spymaster Sir Francis Walsingham and used to entrap Mary for the purpose of removing her as a claimant to the English throne. The plot involved solicitation of a Spanish invasion of England with the purpose of deposing Protestant Queen Elizabeth and replacing her with Catholic Queen Mary and a plot to assassinate Queen Elizabeth.

Anthony Babington

John Ballarad

The chief conspirators were Anthony Babington and John Ballard. Babington was recruited by Ballard, a Jesuit priest who hoped to rescue the Scottish Queen. Working for Walsingham were double agents Robert Poley and Gilbert Gifford, as well as Thomas Phelippes, a spy agent and cryptanalyst, and the puritan spy Maliverey Catilyn. The turbulent Catholic deacon Gifford had been in Walsingham's service since the end of 1585 or the beginning of 1586. Gifford obtained a letter of introduction to Queen Mary from a confidant and spy for her, Thomas Morgan. Walsingham then placed double agent Gifford and spy decipherer Phelippes inside Chartley Castle, where Queen Mary was imprisoned.

On 7 July 1586, the only Babington letter that was sent to Mary was decoded by Phelippes. Mary responded in code on 17 July 1586 ordering the would-be rescuers to assassinate Queen Elizabeth. The response letter also included deciphered phrases indicating her desire to be rescued: "The affairs being thus prepared" and "I may suddenly be transported out of this place". At the Fotheringay trial in October 1586, William Cecil and Walsingham used the letter against Mary who refused to admit that she was guilty. In the end, she was betrayed by her secretaries who confessed under pressure that the letter was mainly truthful.

The issuance of the papal bull Regnans in Excelsis by Pope Pius V on 25 February 1570, granted English Catholics authority to overthrow the English queen. Queen Mary became the focal point of numerous plots and intrigues to restore England to its former religion, Catholicism, and to depose Elizabeth and even to take her life.

Reacting to the growing threat posed by Catholics, urged on by the pope and other Catholic monarchs in Europe, Francis Walsingham, and William Cecil realised that if Mary could be implicated in a plot to assassinate Elizabeth, she could be executed and the papist threat diminished. Walsingham used Babington to ensnare Queen Mary by sending his double agent, Gilbert Gifford to Paris to obtain the confidence of Morgan, then locked in the Bastille. Morgan previously worked for the 6th Earl of Shrewsbury, an earlier jailor of Queen Mary. Through Shrewsbury, Queen Mary became acquainted with Morgan. Queen Mary sent Morgan to Paris to deliver letters to the French court. While in Paris, Morgan became involved in a previous plot designed by William Parry, which resulted in Morgan's incarceration in the Bastille. In 1585 Gifford was arrested returning to England while coming through Rye in Sussex with letters of introduction from Morgan to Queen Mary. Walsingham released Gifford to work as a double agent, in the Babington Plot. Gifford used the alias "No. 4" and functioned as a courier in the entrapment plot against Queen Mary. Unfortunately for the conspirators, Walsingham was certainly aware of some of the aspects of the plot, based on reports by his spies, most notably Gilbert Gifford, who kept tabs on all the major participants. While he could have shut down some part of the plot and arrested some of those involved within reach, he still lacked any piece of evidence that would prove Queen Mary's active participation in the plot and he feared to commit any mistake which might cost Elizabeth her life.

After the Throckmorton Plot, Queen Elizabeth had issued a decree in July 1584, which prevented all communication to and from Mary. However, Walsingham and Cecil realised that that decree also impaired their ability to entrap Mary. They needed evidence for which she could be executed based on their Bond of Association tenets. Thus Walsingham established a new line of communication, one which he could carefully control without incurring any suspicion from Mary. Gifford approached the French ambassador to England, Baron de Châteauneuf-sur-Cher, and described the new correspondence arrangement that had been designed by Walsingham. Gifford and Mary’s jailer had arranged for a local brewer to facilitate the movement of messages between Queen Mary and her supporters by placing them in a watertight casing inside the stopper of a beer barrel. Thomas Phelippes, a cipher and language expert in Walsingham's employ, was then quartered at Chartley Hall to receive the messages, decode them and send them to Walsingham. Gifford submitted a code table (supplied by Walsingham) to Chateauneuf and requested the first message be sent to Mary.

All subsequent messages to Mary would be sent via diplomatic packets to Chateauneuf, who then passed them onto Gifford. Gifford would pass them on to Walsingham, who would confide them to Phelippes. The cipher used was a substitution cipher. Phelippes would decode and make a copy of the letter. The letter was then resealed and given back to Gifford, who would pass it on to the brewer. The brewer would then smuggle the letter to Mary. If Mary sent a letter to her supporters, it would go through the reverse process. In short order, every message coming to and from Chartley Hall was intercepted and read by Walsingham.

On 14 July 1586, Mary was in a dark mood knowing that her son had betrayed her in favour of Elizabeth, and three days later she replied to Babington in a long letter in which she outlined the components of a successful rescue and the need to assassinate Elizabeth. She also stressed the necessity of foreign aid if the rescue attempt was to succeed.

Mary was clear in her support for the murder of Elizabeth if that would have led to her liberty and Catholic domination of England. In addition, Queen Mary supported in that letter, and in another one to Ambassador Mendoza, a Spanish invasion of England.

The letter was again intercepted and deciphered by Phelippes. But this time, Phelippes, on the direction of Walsingham, kept the original and made a copy, adding a request for the names of the conspirators.

Then, a letter was sent that would destroy Mary's life.

Let the great plot commence.

Signed Mary

On 11 August 1586, after being implicated in the Babington Plot, Mary was arrested while out riding and taken to Tixall Hall. In a successful attempt to entrap her, Walsingham had deliberately arranged for Mary's letters to be smuggled out of Chartley. Mary was misled into thinking her letters were secure, while in reality they were deciphered and read by Walsingham. From these letters, it was clear that Mary was complicit in the plots to dispose of Elizabeth.

In October, she was put on trial for treason under the Act for the Queen's Safety before a court of 36 noblemen. Spirited in her defence, Mary denied the charges. She protested that she had been denied the opportunity to review the evidence, that her papers had been removed from her, that she was denied access to legal counsel and that as a foreign anointed queen she had never been an English subject and thus could not be convicted of treason.

She was convicted on 25 October and sentenced to death with only one commissioner, Lord Zouche, expressing any form of dissent. Nevertheless, Elizabeth hesitated to order her execution, even in the face of pressure from the English Parliament to carry out the sentence. She was concerned that the killing of a queen set a discreditable precedent and was fearful of the consequences, especially if, in retaliation, Mary's son, James, formed an alliance with the Catholic powers and invaded England.

Elizabeth asked Mary's final custodian if he would discreetly kill Mary in a painless manner, which he refused to do in regards to his conscience. On 1 February 1587, Elizabeth signed the death warrant, and entrusted it to William Davison, a privy councillor. On 3 February, ten members of the Privy Council of England, having been summoned by Cecil without Elizabeth's knowledge, decided to carry out the sentence at once. Although today, many historians debate if Elizabeth truly did not want to sign the deaf warrant or if this was simply an attempt to wash Elizabeth's hands from being solely involved in Mary's death.

At Fotheringhay, on the evening of 7 February 1587, Mary was told she was to be executed the next morning. She spent the last hours of her life in prayer, distributing her belongings to her household, and writing her will and a letter to the King of France.

During the execution, her servants, Jane Kennedy and Elizabeth Curle, and the executioners helped Mary remove her outer garments, revealing a velvet petticoat and a pair of sleeves in crimson brown, the liturgical colour of martyrdom in the Catholic Church.

Mary was not beheaded with a single strike. The first blow missed her neck and struck the back of her head. The second blow severed the neck, except for a small bit of sinew, which the executioner cut through using the axe.

Cecil's nephew reported that after her death, a small dog, a Skye terrier owned by the queen, emerged from hiding among her skirts, whimpering. The dog had likely snuck into the hall from under her skirts. It’s said that the dog refused to eat and pined away and died. Everything touched by her blood was supposedly burnt in the fireplace of the Great Hall to obstruct relic hunters. Hence any items that were claimed to be used in her execution or owned by her do not carry sufficient claim of that truth.

A skye terrier

When the news of the execution reached Elizabeth, she became indignant and asserted that Davison had disobeyed her instructions not to part with the warrant and that the Privy Council had acted without her authority. Davison was arrested, thrown into the Tower of London, and found guilty of misprision. He was released nineteen months later, after Cecil and Walsingham interceded on his behalf.

Mary's request to be buried in France was refused by Elizabeth. Her body was embalmed and left in a secure lead coffin until her burial in a Protestant service in late July 1587.